Life Extension Magazine®

Even if you’re exposed to solar rays for just a few minutes a day, photons in the sun’s ultraviolet rays can wreak havoc on your skin, leading to wrinkles, age spots, and cancer.

Most people think that topical sunscreen is the best way to protect against the negative effects of ultraviolet radiation. But even if you faithfully apply sunscreen daily, some parts of your body remain vulnerable to the skin-aging and DNA-damaging effects of the sun.

Fortunately, there is an additional way to protect your skin.

A natural plant compound works at a deep level inside your skin’s cells to reduce the effects of harmful ultraviolet rays and blunt skin aging.1-3

Polypodium leucotomos is a tropical fern extract containing a natural mixture of phytochemicals that have been shown to inhibit photoaging.4-6 It inhibits a protein-degrading enzyme that is a prime cause of photoaging.7 Most strikingly—it exerts its effects when taken orally.4,5

In this article, you’ll learn how this plant extract significantly prevents4,5 —and even repairs5 —the ravages of ultraviolet radiation that lead to premature skin aging.

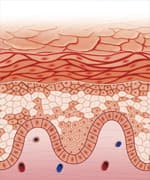

How The Sun Ages Your Skin

Your skin is exposed to the damaging rays of the sun far more than you realize. Even if you’re only in the sun a few minutes a day, the photons (gamma rays) in the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) rays can alter the structure of your skin7 —leading to premature skin aging, wrinkles, sun spots, and more. UV rays are extremely damaging to your skin in a number of ways:

- The photons in the sun’s UV rays oxidize proteins, which correlates with accelerated or premature aging.8-10 Oxidation from UV radiation activates matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), enzymes that break down elastin and collagen—the proteins responsible for keeping your skin supple and firm.11,12

- UV radiation induces oxidative stress that triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors, which further alter elastin and collagen. The result is accumulated breakdown of the skin’s structural integrity.11

- UV rays generate free radicals and other harmful substances that damage DNA. The DNA encodes the information responsible for the continuing production of healthy new skin cells.13

- Ultraviolet radiation reduces skin levels of Langerhans cells, specialized immune cells that are abundantly found in the skin and are responsible for protecting against invading pathogens and for participating in the immune response and defense against cancers.13-16

These destructive effects on tissue structure are eventually visible as photo-aged skin. The prominent clinical sign is wrinkling, but other effects include a loss of elasticity, age spots, hypo- or hyper-pigmentation, spider veins, and blackheads.17

Some people currently rely totally on topical sunscreens—but scientists have found this protection alone to be largely inadequate.17-19

The good news is that scientists have now established that an extract of the fern Polypodium leucotomos contains a high percentage of photo-protective compounds that block the skin aging that results from sun exposure.5

Unleash Your Skin’s Internal Ultraviolet Defenses

For centuries, Honduran natives have protected themselves against sun damage and skin disorders by ingesting Polypodium leucotomos fern extract. The first report on its effectiveness was published 47 years ago in the journal Nature,20 and since then, clinical trials have demonstrated that this antioxidant-rich extract safely bolsters the skin’s defenses against the accelerated aging caused by ultraviolet rays.5

Polypodium leucotomos contains photoprotective compounds—phenols, biological acidic molecules, and monosaccharides—that prevent the sun’s rays from breaking down the body’s own photoprotective molecules. Studies suggest no significant toxicity or allergenic properties.5,6,21

By preserving this natural, built-in protection against sun damage, Polypodium leucotomos exhibits strong anti-aging activity on the skin, both superficial and deeper layers.22

Polypodium leucotomos works in a number of ways to protect the structural integrity of your skin:

- Polypodium leucotomos prevents the destructive structural changes in the skin associated with increased oxidative stress. For example, Polypodium leucotomos inhibits ultraviolet light’s dramatic disorganization of microfilaments—the tough but flexible, fibrous framework that supports skin cells.22

- It also inhibits the ultraviolet light-induced mislocation of adhesion points between cells themselves, and also between cells and the surrounding matrix.22,23 These adhesion points hold separate cells together and provide tissues with structural cohesion and an important signaling pathway—without which skin breakdown may occur.24,25

- Polypodium leucotomos extract helps protect the skin from premature aging by inhibiting several matrix metalloproteinases—enzymes that break down elastin and collagen—and by increasing the expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP), your body’s own inhibitor of metalloproteinase.26,27

- Polypodium leucotomos stimulates molecules that are reduced in the skin during the onset of photoaging—such as elastin, collagen, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta), which is a protein that activates a host of signaling pathways involved in many cellular processes.26,28

- Ultraviolet radiation also damages cellular membranes in the skin by inducing lipidperoxidation.29,30 Polypodium leucotomos extract blocks this process and thus prevents skin damage.31

- Recent research has established the effectiveness of Polypodium leucotomos at naturally protecting both ultraviolet-radiated and non-radiated fibroblasts26 —cells that synthesize the extracellular matrix and collagen, the structural framework of skin tissue.32

- Additionally, extracts of Polypodium leucotomos have been shown to inhibit protein-destroying skin enzymes that decrease skin elasticity,31 to inhibit damaging skin inflammation,33 and to promote the survival of healthy skin cells.22,33

So by protecting from the harmful ultraviolet rays as well as blocking the multiple forms of damage they cause, Polypodium leucotomos extract provides the skin with extraordinary protection from photoaging1,34 —allowing you to retain a high degree of healthy, youthful skin despite chronological aging.2

What You Need To Know

|

Skin Protection From The Inside Out

- Most people assume that the only protection against the skin-aging effects of ultraviolet light must come from topical skin application. But research demonstrates that the oral fern extract Most people assume that the only protection against the skin-aging effects of ultraviolet light must come from topical skin application. But research demonstrates that the oral fern extract Polypodium leucotomos works deep inside the skin to protect against ultraviolet rays and reduce skin aging.

- Sunscreens are an important defense, but most people apply them too lightly and inconsistently.

- Numerous studies indicate that Numerous studies indicate that Polypodium leucotomos inhibits inhibits degradative matrix remodeling, a main cause of photoaging. Most remarkable—it exerts these effects when taken orally.

- This novel extract inhibits—and even repairs—the ultraviolet damage that prematurely ages the skin. Oral This novel extract inhibits—and even repairs—the ultraviolet damage that prematurely ages the skin. Oral Polypodium leucotomos is the most potent tool for preventing photoaged skin, especially when used with topical sunscreen for complete protection.

Restore Sun-Damaged Skin

Remarkably, scientists found that Polypodium leucotomos not only prevents, but also repairs, the sun’s damaging effects on the skin. It prevents sun-aged skin by directly inhibiting MMP (matrix metalloproteinase) expression, preventing the breakdown of collagen in the first place. It repairs sun-aged skin by stimulating new production of collagen and elastin5,31,32 —healing and regenerating photoaged skin after exposure to ultraviolet radiation.5

The regenerative properties underlying this anti-aging effect include reactive oxygen species scavenging capability, inhibiting premature apoptosis (cell death), and blocking improper extracellular matrix rearrangements that occur during oxidative damage.5 These activities suggested to scientists that the benefits of Polypodium leucotomos may extend beyond skin care—and may be useful as a systemic anti-aging and antioxidant tool.5

In fact, scientists already suggest looking beyond the anti-aging effects of Polypodium leucotomos on the skin—and towards future research on its effects on other parameters related to body aging, such telomere length and telomerase activity.5

Four Problems With Sunscreens

The first problem with relying on sunscreens alone for skin protection is finding one that works. The only truly effective sunscreens are those that provide equal protection across the full range of ultraviolet B (UVB) and ultraviolet A (UVA) light.54 Protecting against both is vital because short wavelength UVB injures the outer layers of the skin (epidermis), while long wavelength UVA damages deeper layers of the skin (dermis).55

Second, studies demonstrate that most people apply sunscreen incorrectly and fail to consistently reapply when required—and further demonstrate that it is still important to avoid unnecessary sun exposure after its application.17-19 Many consumers apply only 25 to 50% of the amount used for SPF testing.18 This results in an SPF that is 50% or less effective than the labeled SPF.18

A third problem with sunscreens was underscored by a 2014 study showing that infrared radiation (IR)—which is outside the ultraviolet range—can also contribute to skin photoaging. Sunscreens do not generally protect against infrared radiation, and scientists have been scrambling to develop products that do.56

Finally, no matter how effective and properly applied, topical sunscreens do not provide uniform, total-body surface protection—leaving the eyes, lips, and scalp open to damage by the sun’s rays.

To block photoaging, sunscreens should always be carefully selected, applied in appropriate doses, reapplied at correct intervals, and used in conjunction with other photoprotective measures,54 such as shade, clothing—and ideally, an internal, whole-body protective option.

Powerful Skin Health Benefits

In an array of studies, Polypodium leucotomos has proven its ability to block the long-term skin-aging consequences of sun exposure—but the short-term benefits are equally impressive. This is specifically demonstrated with sunburn, idiopathic dermatoses, and skin cancer.

Sunburn

In the same way that oral Polypodium leucotomos extract can block long-term sun-induced skin aging, it will also help prevent the shorter-term skin damage known as sunburn, which over time greatly contributes to skin photoaging.

If you’re used to covering up or using topical sunscreens, it may be difficult to imagine that swallowing a capsule could provide potent protection from harmful ultraviolet radiation from inside the skin. But multiple studies show that Polypodium leucotomos might increase the amount of time you can spend in the sun before your skin becomes red and inflamed.1,2,34

In an early clinical trial, 21 study participants experienced an almost 3-fold increase in the amount of UV radiation that would generate comparable redness/sunburn, compared to when they used no form of UV protection.2 Those who took special drugs that increase photosensitivity experienced impressive results, in this case increasing the amount of UV radiation before visible suntan occurred by up to nearly 7 fold.2,35

In another study, scientists enlisted volunteers who had fair-to-light skin, which made them more naturally vulnerable to sunburn. The active group received Polypodium leucotomos extract in doses equivalent to 7.5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight—translating to 525 milligrams per 154-pound person—and was then directly exposed to varying doses of artificial ultraviolet radiation. Compared to control subjects, individuals taking Polypodium leucotomos extract experienced a substantial decrease in skin reddening.1

Microscopic effects are even more impressive. Extract-treated cells showed reduced skin damage caused by ultraviolet light—including significantly fewer sunburn cells, which are indicators of tissue injury.1 They also showed a decreased level of the kind of DNA damage that can lead to cancer, as well as a trend suggesting the preservation of Langerhans cells (key immune cells found in the epidermis, or outer layer of skin).1

Idiopathic Dermatoses

While sunburn is an inflammatory reaction with a known cause, some people are prone to specific skin disorders where the cause is unknown, called idiopathic dermatoses. This category can include polymorphic light eruption, a condition in which sufferers experience a skin rash after even brief exposure to sunlight.

In one study, when scientists gave idiopathic photodermatoses patients 480 milligrams per day of oral Polypodium leucotomos and then exposed them to sunlight, an astounding 80% of treated patients reported improvement.36

And in a more recent study of 57 patients with idiopathic photodermatoses, when subjects orally took 480 milligrams of Polypodium leucotomos daily and then exposed themselves to sunlight, 73% oft he patients experienced a significant reduction in symptoms.37

Skin Cancer

The same sunlight that leads to structural changes and accelerated skin aging can trigger changes that boost the risk of skin cancer.38 Even though skin cancer now accounts for over 40% of all US cancers,39 unprotected ultraviolet light exposure is the most preventable risk factor for skin cancer.40 Fortunately, the same mechanisms through which Polypodium leucotomos protects the skin from photoaging provide unprecedented defense against skin cancer as well.1,6,29,31,34,41-44

Scientists found that oral Polypodium leucotomos appears to promote skin health by maintaining the skin’s Langerhans cells, which scavenge toxins and debris.1,2 They also found that the oral extract reduces ultraviolet light-induced DNA damage and mutations associated with skin cancer,1,45 concluding that oral Polypodium leucotomos is “…an effective systemic chemophotoprotective agent...”2

Chronological Aging Versus Photoaging

Chronological aging of the skin is predetermined by each individual’s physiological predisposition.

Sun-induced aging of the skin—or photoaging—varies with the degree of sun exposure and the amount of melanin in the skin.

Chronological aging of the skin is characterized by laxity and fine wrinkles, as well as possible development of benign growths such as seborrheic keratoses and angiomas. However, chronological aging is not associated with increased or decreased pigmentation or with the very deep wrinkles that are characteristic of photoaging.57 This form of skin aging can occur anywhere on the body.

Sun-induced photoaging is clinically characterized by deep wrinkles, as well as mottled pigmentation, rough skin, skin tone loss, dryness, sallowness, deep furrows, severe atrophy, spider veins, laxity, leathery appearance, marked loss of elasticity, actinic purpura (purple spots), precancerous lesions, and possibly skin cancer, including melanoma.58,59 The accelerated aging of skin—photoaging—occurs most often on sun-exposed areas of the skin, such as the face, neck, upper chest, hands, and forearms.60

Seborrheic keratoses —small, benign, wart-like growths—are regarded as a key biomarker of chronological or intrinsic skin aging.57,60 They are not caused by, and appear independently of, sun exposure.

Vascular lesions —such as broken blood vessels, facial veins, rosacea, telangiectasias, and many other kinds of vascular blemishes—are regarded as a key biomarker of photoaging. They are not caused by, and appear independently of, intrinsic aging. Studies in humans and in mice have demonstrated that acute and chronic ultraviolet B (UVB) irradiation greatly increases skin angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels from existing vessels).61-63

Enhancing The Photo-Protective Effects Of Polypodium Leucotomos

Scientists were intrigued to identify a specific extract that further enhances the potent photoprotective effects of Polypodium leucotomos. Obtained from three red orange varieties (Citrus sinensis var. Moro, Tarocco, and Sanguinello), this extract is known as Red Orange Complex and provides abundant phenolic compounds, including anthocyanins, flavanones, ascorbic acid, and hydroxycinnamic acids.46-48

Early lab studies indicated that Red Orange Complex exerts an anti-inflammatory effect on human cells, including keratinocyte cells48 —the predominant cell type in the epidermis. In cell culture studies, this complex has been shown to inhibit the growth and development of human cancer cells49 and to inhibit cell death caused by UVB rays.50

In addition, in vivo research demonstrated that Red Orange Complex provides topical photoprotection against UVB-induced skin redness.46,51 Supplementation was also found to increase serum thiol groups—which are free-radical quenchers—in individuals exposed to significant automobile exhaust pollution in the workplace52 and were also found to reduce oxidative stress in type II diabetic patients.53

Encouraged by these results, scientists conducted a clinical trial to study the complex’s photoprotective capacity. Enrolling 18 volunteers, the study team measured the effects of oral Red Orange Complex supplementation on UVB-induced damage. After 15 days, the intensity of the induced redness decreased by about 35%—demonstrating significant sun protection for the skin.51

These various outcomes demonstrate that Red Orange Complex supports Polypodium leucotomos to further inhibit the aging effects of ultraviolet radiation on the skin.

Topical Versus Oral Sunscreen

|

Sunscreens are generally applied in insufficient dosages such that the effective SPF is 50% or less than the labeled SPF18 and they’re seldom reapplied as required. Sunscreens do not generally block infrared radiation.56,63 Also, few people are in the habit of wearing sunscreen on cloudy days—but radiation scattering by clouds can result in higher total radiation levels on partly cloudy days than on completely sunny days. In fact, 80% of ultraviolet light can penetrate light cloud cover.64

Oral Polypodium leucotomos tropical fern extract can block UV and IR radiation at the cellular level and can inhibit the many cellular skin photoaging effects.2,5,22,26,31,33,34

Sunscreens have one key mechanism: they function at the skin surface by limiting the amount of solar radiation that penetrates deeper to trigger photoaging.

Oral Polypodium leucotomos is active at multiple levels—from the skin surface to deep inside and in between skin cells, exerting broad effects that protect skin from the effects of radiation. Working through multiple mechanisms, Polypodium leucotomos reduces photoaging by:2,5,22,26,31,33,34

- Preventing decomposition of the body’s photoprotective molecules

- Reducing the remodeling of the tissue matrix

- Inhibiting oxidative stress-induced morphological (structural, form-related) changes

- Preventing radiation-induced loss of cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix anchorage points

- Inhibiting several matrix metalloproteinases

- Stimulating an endogenous tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)

- Reducing lipid peroxidation

- Protecting fibroblasts

- Inhibiting elasticity-decreasing enzymes

- Lowering inflammation

- Inhibiting apoptosis

- Scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS)

- Repairing photoaging damage by stimulating elastin, collagen, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta), and

- Preventing DNA damage.

Summary

Many people assume that protection from the skin-wrinkling effects of ultraviolet radiation must occur outside the body—but clinical research shows that an oral extract of the fern Polypodium leucotomos works deep inside the skin to protect against ultraviolet rays and block skin aging.1-3

Polypodium leucotomos has been shown in numerous studies4,5 to inhibit degradative matrix remodeling, a main cause of photoaging.6 And most striking—it exerts these effects when taken orally.4,5

This novel extract helps prevent4,5 —and even repair5 —ultraviolet radiation damage that prematurely ages the skin.

The most effective program to protect against the accelerated skin aging (photoaging) involves limited exposure to sunlight (especially between noon and 2:00 p.m.), liberal application and reapplication of a quality topical sunscreen, and regular oral supplementation with Polypodium leucotomos fern extract with Red Orange Complex to further enhance the fern extract’s effectiveness.

If you have any questions on the scientific content of this article, please call a Life Extension® Health Advisor at 1-866-864-3027.

Understanding The Sun’s Wavelengths

|

Different wavelengths of sunlight radiation represent different risks as follows:65

- UVC rays —wavelengths of which range from 180 to 280 nanometers—are almost completely absorbed by the ozone layer and do not affect the skin.

- UVB rays —wavelengths of which range from 280 to 325 nanometers and which are strongest around midday—affect the superficial layer of the skin known as the epidermis and causes sunburn.57

- UVA rays —wavelengths of which range from 315 to 400 nanometers—were believed to have a minor effect on the skin, but studies now show that UVA penetrates deeper into the skin. UVA also makes up about 95% of sunlight, while UVB makes up about 5% of sunlight, and therefore, UVA causes more severe skin aging damage.57,66-68

- IR or infrared radiation—wavelengths of which range from 760 nanometers to one millimeter—has only recently been determined to induce skin photoaging and skin damage.56,63,69 While the proton energy of infrared is low, the total amount of infrared that reaches human skin is massive compared to ultraviolet radiation. Most IR lies within the IR-A band—ranging between 760 nanometers and 1,440 nanometers—a band of IR that represents about 30% of total solar energy. IR-A penetrates human skin deeply with 50% of it reaching the dermis skin layer.57

References

- Middelkamp-Hup M, Pathak MA, Parrado C, et.al. Oral Polypodium leucotomos extract decreases ultraviolet-induced damage of human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Dec;51(6):910-8.

- González S, Pathak MA, Cuevas J, Villarrubia VG, Fitzpatrick TB. Topical or oral administration with an extract of Polypodium leucotomos prevents acute sunburn and psoralen-induced phototoxic reactions as well as depletion of Langerhans cells in human skin. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1997 Feb-Apr;13(1-2):50-60.

- González S, Gilaberte Y, Philips N. Mechanistic insights in the use of a Polypodium leucotomos extract as an oral and topical photoprotective agent. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010 Apr;9(4):559-63.

- González S, Gilaberte Y, Philips N. Mechanistic insights in the use of a Polypodium leucotomos extract as an oral and topical photoprotective agent. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010 Apr;9(4):559-63.

- González S, Gilaberte Y, Philips N, Juarranz A. Fernblock, a nutriceutical with photoprotective properties and potential preventive agent for skin photoaging and photoinduced skin cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(12):8466-75.

- González S, Alonso-Lebrero JL, Del Rio R, Jaen P. Polypodium leucotomos extract: a nutraceutical with photoprotective properties. Drugs Today (Barc). 2007 Jul;43(7):475-85.

- Fisher GJ, Datta SC, Talwar HS, et al. Molecular basis of sun-induced premature skin ageing and retinoid antagonism. Nature. 1996 Jan 25;379(6563):335-9.

- Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation and aging. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:1250-8.

- Gueranger Q, Li F, Peacock M, et al.Protein Oxidation and DNA Repair Inhibition by 6-Thioguanine and UVA Radiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Nov 27. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.509. [Epub ahead of print]

- Schweikert K, Gafner F, Dell’Acqua G.A bioactive complex to protect proteins from UV-induced oxidation in human epidermis. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2010 Feb;32(1):29-34.

- Chen L, Hu JY, Wang SQ. The role of antioxidants in photoprotection: a critical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1013-24.

- Knaggs H. A new source of aging? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009 Jun;8(2):77-82.

- Lee CH, Wu SB, Hong CH, Yu HS, Wei YH. Molecular mechanisms of UV-induced apoptosis and its effects on skin residential cells: The implication in UV-based phototherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2013 Mar 20;14(3):6414-35.

- Kölgen W , Both H, van Weelden H, et al. Epidermal langerhans cell depletion after artificial ultraviolet B irradiation of human skin in vivo: apoptosis versus migration. J Invest Dermatol. 2002 May;118(5):812-7.

- Le Poole IC, ElMasri WM, Denman CJ, et al. Langerhans cells and dendritic cells are cytotoxic towards HPV16 E6 and E7 expressing target cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother . 2008 Jun;57(6):789-97.

- Nakano T, Oka K, Sugita T, Tsunemoto H. Antitumor activity of Langerhans cells in radiation therapy for cervical cancer and its modulation with SPG administration. In Vivo . 1993 May-Jun;7(3):257-63.

- Jansen R, Wang SQ, Burnett M, Osterwalder U, Lim HW. Photoprotection: part I. Photoprotection by naturally occurring, physical, and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Dec;69(6):853.e1-12; quiz 865-6.

- Wang SQ, Dusza SW. Assessment of sunscreen knowledge: a pilot survey. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(Suppl 3):28-32.

- Thieden E, Philipsen PA, Sandby-Moller J, Wulf HC. Sunscreen use related to UV exposure, age, sex, and occupation based on personal dosimeter readings and sun-exposure behavior diaries. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:967-73.

- Horvath A, Alvarado F, Szöcs J, de Alvardo ZN, Padilla G. Metabolic effects of calagualine, an antitumoral saponine of Polypodium leucotomos. Nature. 1967 Jun 17; 214(5094):1256-8.

- Gonzalez S, Gilaberte Y, Philips N, Juarranz A. Fernblock, a nutriceutical with photoprotective properties and potential preventive agent for skin photoaging and photoinduced skin cancers. Int J Mol Sci . 2011;12(12):8466-75.

- Alonso-Lebrero JL, Domínguez-Jiménez C, Tejedor R, Brieva A, Pivel JP. Photoprotective properties of a hydrophilic extract of the fern Polypodium leucotomos on human skin cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2003;70:31-7.

- Available at: http://jcs.biologists.org/content/124/8/1183.full.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- Yan HH, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Cross-talk between tight and anchoring junctions-lesson from the testis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;636:234-54.

- Kezic S, Novak N, Jasaka I, et al. Skin barrier in atopic dermatitis. Front Biosc (Landmark Ed). 2014 Jan 1;19:542-56.

- Philips N, Conte J, Chen YJ, et al. Beneficial regulation of matrixmetalloproteinases and their inhibitors, fibrillar collagens and transforming growth factor-beta by Polypodium leucotomos, directly or in dermal fibroblasts, ultraviolet radiated fibroblasts, and melanoma cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:487-95.

- Murphy G, Cockett MI, Ward RV, Docherty AJ. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of elastin, type IV collagen and proteoglycan. A quantitative comparison of the activities of 95 kDa and 72 kDa gelatinases, stromelysins-1 and -2 and punctuated metalloproteinase (PUMP). Biochem J . 1991 Jul 1;277 ( Pt 1):277-9.

- Wrighton KH, Lin X, Feng XH. Phospho-control of TGF-beta superfamily signaling. Cell Res . 2009 Jan;19(1):8-20.

- Briganti S, Picardo M. Antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation and skin diseases. What’s new. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:663-9.

- Perez S, Sergent O, Morel P, et al. Kinetics of lipid peroxidation induced by UV beta rays in human keratinocyte and fibroblast cultures. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil . 1995;189(3):453-65.

- Philips N, Smith J, Keller T, Gonzalez S. Predominant effects of Polypodium leucotomos on membrane integrity, lipid peroxidation, and expression of elastin and matrixmetalloproteinase-1 in ultraviolet radiation exposed fibroblasts, and keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci. 2003;32:1-9.

- Available at: http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/glossary=fibroblast. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- Jaczyk A, Garcia-Lopez MA, Fernandez-Peñas P, et al. A Polypodium leucotomos extract inhibits solar-simulated radiation-induced TNF-alpha and iNOS expression, transcriptional activation and apoptosis. Exp Dermatol. 2007 Oct;16(10):823-9.

- Middelkamp-Hup MA, Pathak MA, Parrado C, et al. Orally administered Polypodium leucotomos extract decreases psoralen-UVA-induced phototoxicity, pigmentation, and damage of human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Jan;50(1):41-9.

- Ravnbak MH 1, Wulf HC. Pigmentation after single and multiple UV-exposures depending on UV-spectrum. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007 Apr;299(1):25-32. Epub 2007 Jan 26.

- Caccialanza M, Percivalle S, Piccinno R, Brambilla R. Photoprotective activity of oral Polypodium leucotomos extract in 25 patients with idiopathic photodermatoses. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007 Feb;23(1):46-7.

- Caccialanza M, Recalcati S, Piccinno R. Oral Polypodium leucotomos extract photoprotective activity in 57 patients with idiopathic photodermatoses. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011 Apr;146(2):85-7.

- Ichihashi M, Ueda M, Budiyanto A, et al. UV-induced skin damage. Toxicology. 2003 Jul 15;189(1-2):21-39.

- Available at: http://www.epa.gov/sunwise/uvandhealth.html. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/excite/skincancer/mod10.htm. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- González S, Pathak MA. Inhibition of ultraviolet-induced formation of reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, erythema and skin photosensitization by Polypodium leucotomos. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996 Apr;12(2):45-56.

- Siscovick JR, Zapolanski T, Magro C, et al. Polypodium leucotomos inhibits ultraviolet B radiation-induced immunosuppression. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008 Jun;24(3):134-41.

- Gonzalez S, Alcaraz MV, Cuevas J, et al. An extract of the fern Polypodium leucotomos (Difur) modulates Th1/Th2 cytokines balance in vitro and appears to exhibit anti-angiogenic activities in vivo: pathogenic relationships and therapeutic implications. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(3A):1567-75.

- Rodríguez-Yanes E, Juarranz Á, Cuevas J, Gonzalez S, Mallol J. Polypodium leucotomos decreases UV-induced epidermal cell proliferation and enhances p53 expression and plasma antioxidant capacity in hairless mice. Exp Dermatol. 2012 Aug;21(8):638-40.

- Emanuel P, Scheinfeld N. A review of DNA repair and possible DNA-repair adjuvants and selected natural anti-oxidants. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13(3):10.

- Bonina FP, Saija A, Tomaino A, Lo Cascio R, Rapisarda P, Dederen JC, In vitro antioxidant activity and in vivo photoprotective effect of red orange extract. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1998;20:331-42.

- Rapisarda P, Tomaino A, Lo Cascio R, Bonina F, De Pasquale A, Saija A. Antioxidant effectiveness as influenced by phenolic content of fresh orange juices. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:4718-23.

- Venera C, Frasca G, Rizza L, Rapisarda P, Bonina F. Antiinflammatory effects of a red orange extract in human keratinocytes treated with interferon-gamma and histamine. Phytother Res. 2010;24:414-8.

- Vitali F, Pennisi C, Tomaino A, et al. Effect of a standardized extract of red orange juice on proliferation of human prostate cells in vitro. Fitoterapia. 2006 Apr;77(3):151-5.

- Cimino F, Cristania M, Saijaa A, Bonina FP, Virgili F. Protective effects of a red orange extract on UVB-induced damage in human keratinocytes. BioFactors. 2007;30:129-38.

- Bonina FP. Effect of the supplementation with Red Orange Complex® on ultraviolet-induced skin damage in human volunteers. Bionap Report . Santa Venerina, CT, Italy, 2008.

- Bonina FP, Puglia C, Frasca G, et al. Protective effects of a standardized red orange extract on air pollution-induced oxidative damage in traffic police officers. Nat Prod Res. 2008;22(17,20):1544-51.

- Bonina FP, Leotta C, Scalia G, et al. Evaluation of oxidative stress in diabetic patients after supplementation with a standardised red orange extract. Diab Nutr Metab. 2002;15:14-9.

- Jansen R, Osterwalder U, Wang SQ, Burnett M, Lim HW. Photoprotection: part II. Sunscreen: development, efficacy, and controversies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Dec;69(6):867.e1-14; quiz 881-2.

- Herrling T, Fuchs J, Rehberg J, Groth N. UV-induced free radicals in the skin detected by ESR spectroscopy and imaging using nitroxides. Free Radical Biol Med. 2003;35(1):59–67.

- Grether-Beck S, Marini A, Jaenicke T, Krutmann J. Photoprotection of human skin beyond ultraviolet radiation. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. Epub 2014 Jan 16. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12111.

- Pandel R, Poljšak B, Godic A, Dahmane R. Skin Photoaging and the Role of Antioxidants in Its Prevention. ISRN Dermatol. 2013 Sep 12;2013:930164.

- Yaar M, Eller MS, Gilchrest BA. Fifty years of skin aging. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. 2002;7(1):51-8.

- Gilchrest BA. Skin aging and photoaging. Dermatology Nursing. 1990;2(2):79-82.

- Helfrich YR, Sachs DL, Voorhees JJ. Overview of skin aging and photoaging. Dermatology Nursing. 2008;20(3):177-184.

- Bielenberg DR, Bucana CD, Sanchez R, Donawho CK, Kripke ML, Fidler IJ. Molecular regulation of UVB-induced cutaneous angiogenesis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1998;111(5):864-72.

- Yano K, Oura H, Detmar M. Targeted overexpression of the angiogenesis inhibitor thrombospondin-1 in the epidermis of transgenic mice prevents ultraviolet-B-induced angiogenesis and cutaneous photo-damage. J Investigative Dermato. 2002;118(5):800-5.

- Meinke MC, Haag SF, Schanzer S, Groth N, Gersonde I, Lademann J. Radical protection by sunscreens in the infrared spectral range. Photochem Photobiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;87(2):452-6.

- Yano K, Kadoya K, Kajiya K, et al. Ultraviolet B irradiation of human skin induces an angiogenic switch that is mediated by upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and by downregulation of thrombospondin-1. Br J Dermatol . 2005 Jan;152(1):115-21.

- Available at: http://www.uvawareness.com/uv-info/uv-strength.php#skies. Accessed April 14, 2014

- Available at http://www.epa.gov/radtown/sun-exposure.html. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- Laurent-Applegate LE, Schwarzkopf S. Photooxidative stress in skin and regulation of gene expression. In: Fuchs J, Packer L, editors. Environmental Stressors in Health and Disease. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker; 2001.

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge J. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. 4th edition. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Schieke SM. Photoaging and infrared radiation. Novel aspects of molecular mechanisms. Hautarzt. 2003 Sep;54(9):822-4.