Life Extension Magazine®

Dropping dead from a heart attack, being crippled by a catastrophic stroke, having limbs amputated as a result of peripheral vascular disease—these are among the frightening consequences of vascular disease, the number-one killer of Americans. Metabolic syndrome and its associated condition of insulin resistance pose a major threat to cardiovascular health that most health care practitioners do not even discuss with their patients. Remarkably, the public knows very little about this silent but deadly condition, and many affected individuals are not even aware that metabolic syndrome is inflicting severe damage to their arteries and brain cells. The news media and health care providers pay almost no attention to the epidemic of insulin resistance, the fundamental cause of metabolic syndrome. To avoid the potentially disastrous cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome, you need to understand:

Gauging Your Risk for Insulin ResistanceMetabolic syndrome is characterized by insulin resistance. Before explaining insulin resistance, we need to understand what insulin is and how it acts in the body. A hormone produced in the pancreas, insulin’s major function is to regulate blood sugar, or glucose, levels. Insulin helps to shuttle glucose molecules from the blood into the cells of the body. When blood sugar levels increase, insulin output increases.

Insulin resistance means that insulin does not work optimally at its target tissue—such as muscle, fat, or liver tissue—to drive glucose into cells. This has numerous adverse consequences, including glucose and insulin levels that are much higher than normal. As the body attempts to overcompensate for poor insulin action by pumping out more insulin from the pancreas, insulin levels rise. Eventually, over time, the pancreas can “burn out” and no longer produce enough insulin to control blood sugar. When insulin levels are not sufficient to bring blood sugar levels down to the normal range, type II diabetes mellitus can result. The gold standard for measuring insulin resistance is a very complex procedure called a “hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp” that is offered at specialized academic medical research centers. In this two-hour procedure, insulin is infused intravenously at a constant rate according to body weight. At the same time, glucose is infused intravenously at a variable rate to balance out the insulin infusion. The rate of glucose infusion into blood during the last 30 minutes of the test determines insulin sensitivity. Fortunately, to help determine your risk of insulin resistance, you do not have to travel to an academic medical center to have the “hyper-insulinemic euglycemic clamp” performed; instead, you need only undergo some simple blood tests. Certain blood tests such as fasting insulin can serve as surrogate markers for insulin resistance. Excess insulin (fasting hyperinsulinemia) is defined when levels equal to or greater than 15 µU/mL are found. These higher fasting insulin levels are associated with insulin resistance.1 Other blood tests that are very useful in evaluating the risk of insulin resistance include serum triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Triglycerides equal to or greater than 130 mg/dL and a triglyceride:HDL ratio equal to or above 3.0 suggest a high risk of insulin resistance.1 In fact, the Life Extension Foundation has consistently advocated even lower levels of triglycerides (less than 100 mg/dL) as being optimal.

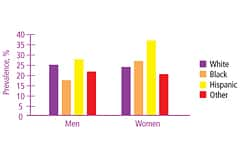

Do You Have Metabolic Syndrome?Afflicting one of every five Americans (with even higher rates in certain ethnic populations), metabolic syndrome has ominous implications for cardiovascular disease risk.2 More than 20 years ago, scientists identified the constellation of conditions that characterizes metabolic syndrome in a group of patients with a drastically elevated risk of heart disease and stroke. Initially called “Syndrome X” by scientists, it is now known as metabolic syndrome. This dangerous condition is characterized by insulin resistance, which leads to abnormally high serum lipids and cholesterol, high blood pressure, abnormally high blood sugar, and increased blood-clotting tendencies.3 Metabolic syndrome dramatically increases cardiovascular disease risk.4 Recent trial results in more than 1,200 men followed for 11 years found that those with metabolic syndrome were up to 360% more likely to die from coronary heart disease.5 The diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome can differ slightly depending on the medical experts consulted. A standard, accepted definition was established by the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III).6 According to its definition, you have metabolic syndrome if you have three or more of the following criteria:

| ||||||

A Program for Averting Metabolic SyndromeThe following step-by-step program can help you avert the potentially deadly consequences of metabolic syndrome. Taking these simple steps can help you lead a long, healthy life and avoid succumbing to a multitude of life-threatening diseases. Step 1: Assess Your Body Composition.The first step involves knowing and understanding your body composition and its importance in helping to prevent metabolic syndrome. Surprisingly, stepping on a scale and seeing what you weigh does not tell very much about your risk of developing metabolic disease. Body mass index (BMI) is a standard measure of overweight and obesity. BMI is obtained by dividing your body weight in kilograms by your height in meters squared (kg/m2). However, BMI fails to account for body composition. Your body composition is a measure of how much lean body mass (muscle) and adipose tissue (body fat) you have. Compare two 40-year-old men, both of whom stand six feet tall and weigh 200 pounds. One man is very muscular (about 7% body fat) and has a waist circumference of 32 inches. By contrast, the other man is out of shape (about 30% body fat) and has a waist circumference of 40 inches. The key point is, both men have the same BMI. Does this mean that both men have the same risk of developing insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome? No!

The man who has poor body composition (low level of lean body mass, high level of fat mass) and carries his body fat around his waist (central obesity) is at risk of developing insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. The physically fit man with a low amount of body fat and a slim waist is at very, very low risk of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.

Unfortunately, many individuals pay more attention to body weight than to body composition. Scientists, however, know better. The easiest surrogate assessment of body composition is central obesity, and the easiest way to determine central obesity is to measure waist circumference—if you have a big waist, your risk of metabolic disease is increased. Step 2: Maintain Good Body Composition.How do you obtain and maintain good body composition? Maintaining lean body mass and decreasing body fat is easier than you think. First, do not fall for the latest fad diet. Maintaining a stable body weight is not magic. Ignore any diet “guru” who promises “magical” weight loss, vilifies “forbidden foods,” and promotes excluding certain food “types” based on the latest round of misunderstood and misinterpreted science. Do not buy into it! Instead, simply eat more whole foods and fewer processed foods. Prioritize eating high-quality foods like salmon, vegetables, wild rice, berries, and citrus fruits. De-emphasize eating foods that are highly processed or of low nutritional value, such as cakes, cookies, bagels, fried chicken, and American cheese. In fact, studies show that diets that emphasize whole foods, such as the Mediterranean diet, help maintain lean body mass while also improving metabolic markers like insulin, cholesterol, fibrinogen, and uric acid.7 Other studies of people eating Mediterranean-type diets show a strong reduction in cholesterol levels, increased psychological and physical well-being, and a trend towards weight loss even without trying to diet.8 A great-tasting, healthy diet is abundant in whole foods, much like the traditional diets of Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean. This style of eating is rich in whole grains, whole fruits, and green vegetables, incorporates low to modest amounts of protein, and is high in “good fats” from sources such as sesame seeds, walnuts, almonds, and olives. Moderate amounts of high-fiber carbohydrates and “good fats” predominate in traditional diets of the Mediterranean, Asia, and Africa. Randomized clinical trials have shown that this type of diet may be best for people at risk for metabolic disease. For example, a trial in patients with type II diabetes mellitus showed better blood sugar control and cholesterol levels in people consuming a diet comprising 40% carbohydrates, 45% fat, and 15% protein compared to those who consumed a diet consisting of 55% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 15% protein.9 In other studies, a diet moderate in carbohydrates and relatively high in monounsaturated fat from olive oil and polyunsaturated fat from fish—such as the Mediterranean diet—actually decreased insulin resistance and inflammation.10 Furthermore, this diet is better than the step I National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) diet in preventing heart disease and stroke.11 Second, if you are not physically active, start moving your body! Simply walking at a brisk pace three to five days each week for at least 20 minutes will help. If and when you get more ambitious, you can engage in more demanding physical activities at a higher level of exertion. In addition, consider weight training to build more muscle mass and to stimulate your metabolism. Step 3: Improve Metabolic Function with Nutritional Supplements.Smart supplementation can have a significant impact on metabolic health. A number of nutritional supplements hold great promise for normalizing blood sugar and metabolic control. Chromium. Chromium is a critically essential cofactor for glucose control. Chromium helps insulin shuttle blood sugar (glucose) into cells. In fact, without chromium, insulin cannot work properly. Unfortunately, most Americans are deficient in this critical nutrient. Some experts believe that Americans ingest less than half the recom-mended daily amount of chromium.12 This may be partly due to the nation’s over-reliance on processed foods, which are generally rich in calories but poor in nutrients. Another factor contributing to widespread chromium deficiency is food grown in soil containing a low content of minerals such as chromium. In fact, the 1992 Earth Summit report showed that North American soils have been depleted of 85% of their mineral content in the past 100 years—the highest rate of mineral depletion in the world.13 Thus, it should come as no surprise that the foods we consume are deficient in trace minerals such as chromium. Some scientists have postulated that rising rates of metabolic syndrome and diabetes in the US may result in part from declining levels of chromium in American soil and diets. Many clinical studies of patients with and without metabolic disease have shown metabolic benefits—including improved blood sugar control, cholesterol, and insulin—with supplemental chromium doses from 200 to 1000 mcg daily.14-17 Recently, a bioavailable and biologically safe form of chromium called chromium 454™ has attracted the attention of nutritional scientists seeking ways to promote metabolic health. Derived from plant and biological extracts, this distinct form of chromium is water soluble, allowing for outstanding absorption. Insulin-deficient diabetic rats that received chromium 454™ for three weeks demonstrated an impressive 38% reduction in blood glucose levels. These findings led scientists to suggest that chromium may provide metabolic support for individuals seeking to optimize their blood glucose levels.18

DHEA. In both middle-aged and older men and women, suboptimal hormone profiles are not unusual. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a critical hormone that is involved in many metabolic processes, both directly and indirectly (through its conversion to testosterone and estrogen). Low levels of DHEA are associated with an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome. For example, a cross-sectional study of 400 men, aged 40-80, showed that the lower the DHEA level, the greater the risk of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.19 DHEA dosing should be individualized based on blood testing. A simple blood test known as DHEA-sulfate (DHEA-S) will provide important information about your DHEA levels. However, even relatively low doses can provide benefit. A study of elderly men and women showed that a daily dose of as little as 50 mg of DHEA for six months was associated with significant fat loss and improvements in insulin sensitivity.20 | ||||

DHA/EPA. The long-chain omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) have a multitude of health benefits, including increased fat burning and improved glucose metabolism.21 In addition, EPA and DHA decrease the expression of genes involved in fat storage,22 down-regulate genes involved in inflammation,23 and lower levels of C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation.24 Be careful, however, if you consume large amounts of fish, as you may be unwittingly ingesting large amounts of mercury, a kidney toxin that is found in high amounts in fish such as swordfish, shark, and even tuna.25,26 Supplementing with a high-quality omega-3 fatty acid product that has been tested and found to be free of contaminants and pollutants is a smart alternative to eating mercury-contaminated fish. Bioflavonoids. Inflammation is an important factor in the development of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.27,28 Bioflavonoids like quercetin, resveratrol, and olive polyphenols have natural anti-inflammatory properties and may offer protection against metabolic syndrome. Quercetin, a potent bioflavonoid found in vegetables, inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines (proteins involved in immunity and inflammation).29 Resveratrol, found in the skin of red fruits like grapes, has been shown to inhibit the expression of genes involved in inflammation better than the potent prescription corticosteroid dexamethasone.30

In addition to having potent anti-inflammatory effects,31 olive polyphenols have beneficial benefits on the cardiovascular system. Studies show that olive polyphenols dramatically increase the resistance of cholesterol to oxidation.36 This is very important, as oxidized cholesterol serves as a trigger for atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).37 Olive polyphenols also benefit the vascular endothelium, the lining of blood vessel walls. Hydroxytyrosol, a principal polyphenol in olives, reduces the “stickiness” of cells in the vascular endothelium.38 Cell “stickiness” may increase the tendency to form blood clots in the arteries. Carotenoids and retinoids. Carotenoids (found in foods like carrots, squash, and tomatoes) and retinoids, which are beneficial to eye health, also play an important role in preventing metabolic disease. Interestingly, experiments in early growth and development show that low vitamin A intake decreases insulin-producing cells,39 pointing to the importance of adequate vitamin A intake for development of the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that even after adjusting for confounding factors like age, sex, ethnicity, education, smoking status, and physical activity, people with metabolic syndrome had significantly lower concentrations of carotenoids and retinyl esters (a type of vitamin A).40 Evidence suggests that there may be a threshold for vitamin A consumption in terms of metabolic benefit. In one study, daily vitamin A intake of more than 10,000 IU significantly lowered blood sugar and insulin levels in healthy human volunteers, while daily intake of less than 8000 IU was associated with higher blood sugar levels.41 Water-soluble cinnamon extracts. Exciting data show that a special extract from cinnamon holds tremendous promise for normalizing blood sugar levels naturally.

A 2003 study of patients with type II diabetes examined the effects of cinnamon on blood sugar. Participants received one, three, or six grams per day of cinnamon or placebo. After 40 days, the three groups receiving cinnamon demonstrated significant reductions in blood sugar of up to 29%, in triglycerides of up to 30%, and in cholesterol of up to 26%.42 So, all you need to do to prevent metabolic disease is consume large amounts of cinnamon, right? Wrong! Whole cinnamon contains volatile oils, which are well-known irritants that may trigger allergic reactions. Even more worrisome is that toxicology studies in mice show that consuming raw cinnamon rich in these oils can cause tumors, including squamous cell papillomas.43 Therefore, the best strategy is to avoid the danger of cinnamon’s volatile oils while still obtaining the remarkable benefits of cinnamon. Fortunately, these oils are not responsible for cinnamon’s impressive effects in stabilizing blood sugar. Instead, cinnamon’s water- soluble polyphenol polymers are the key components responsible for its beneficial metabolic effects.44 The polyphenol type-A polymers from cinnamon up-regulate genes involved in blood sugar control.45 Other cinnamon polyphenol polymers such as methylhydroxychalcone have additional beneficial effects on blood sugar control.46 Recent studies consistently show the anti-diabetic effects of cinnamon extracts in validated animal models of metabolic disease.47,48 Cinnamon extract not only supports healthy blood sugar levels, but also has excellent antioxidant properties. The natural water-soluble cinnamon extract inhibits oxidation even better than the powerful synthetic antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene, or BHT.49 Coffee polyphenols. Who would have ever thought that a water-soluble extract of coffee acts to boost the key target hormone that multi-billion-dollar pharmaceutical companies are targeting as the next breakthrough treatment for metabolic disease? A very large study (14,629 men and women) published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2004 showed that the greater your coffee consumption, the lower your risk of metabolic disease, including type II diabetes mellitus.50 Another very large study that followed 41,934 men showed a similarly powerful association between increased coffee intake and decreased risk of type II diabetes, even after adjusting for age, body mass index, and other risk factors.53

Before you decide to drink a pot of coffee a day or open your own Starbucks, be advised that drinking large amounts of coffee is not the best strategy for preventing metabolic disease. Coffee can cause insomnia and may induce high blood pressure in some people, largely due to its caffeine content. Moreover, results of the 2004 ATTICA study showed that coffee consumption dramatically increases markers of inflammation like C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.54 A smart strategy is to identify and isolate the components of coffee that are responsible for its beneficial effects on metabolism, including blood sugar control. Scientists have found that water extracts of roasted coffee residues, including the primary coffee polyphenols caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid, are key components responsible for coffee’s beneficial metabolic effects. Preclinical studies show that chlorogenic acid improves blood sugar control and decreases cholesterol and triglycerides.55 In human studies, chlorogenic acid, a major polyphenol in water extracts of coffee, has improved the release of hormones critical to blood sugar control. For example, in healthy human volunteers, consuming coffee polyphenols like chlorogenic acid dramatically increased glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secretion.56 This finding is remarkable because several GLP-1-related pharmaceutical agents are targeting this hormone as a treatment for metabolic disease, including the recently FDA-approved GLP-1 analog BYETTA™ (exenatide). Chlorogenic acid acts to increase GLP-1.57 Coffee extracts offer other benefits as well. Water-soluble coffee polyphenols like chlorogenic acid scavenge free radicals and provide powerful protection against lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage by proteins.58

ConclusionWith so much focus on cholesterol, little attention has been paid to the critical role of insulin resistance in the development of cardiovascular disease. Insulin resistance is the root cause of metabolic syndrome, a serious risk factor for heart disease and stroke that has received little attention until recently. Identifying your risk for metabolic syndrome involves only a series of very simple tests. If you are found to be at risk, decreasing your body fat—particularly around your waist—is critically important. Avoid fad diets, eat a whole-food diet like those consumed by Mediterranean cultures, and get some physical exercise—your body will thank you for it! Nutritional supplements can help improve blood sugar control and metabolic health naturally, without danger or stress to your body. Particularly compelling are polyphenol-rich, water-soluble extracts of cinnamon and coffee, along with green tea extract, chromium, and banaba leaf-derived corosolic acid. Documented evidence demonstrates the ability of these agents to help normalize blood sugar levels. Avoiding the perils of metabolic syndrome is simple. First, get tested to see whether you are at risk. If laboratory testing and a physical examination reveal that you are at risk, immediately take the necessary steps—including exercise, a healthy diet, and targeted nutritional strategies—to prevent the dire cardiovascular consequences of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.

| ||||||||||

| References | ||||||||||

| 1. McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, et al. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Nov 18;139(10):802-9. 2. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002 Jan 16;287(3):356-9. 3. Reaven GM. Syndrome X: 6 years later. J Intern Med Suppl. 1994;736:13-22. 4. Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005 Apr 16;365(9468):1415-28. 5. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002 Dec 4;288(21):2709-16. 6. Anon. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002 Dec 17;106(25):3143-421. 7. De LA, Petroni ML, De Luca PP, et al. Use of quality control indices in moderately hypocaloric Mediterranean diet for treatment of obesity. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2001 Aug;14(4):181-8. 8. Castagnetta L, Granata OM, Cusimano R, et al. The Mediet Project. Ann NY Acad.Sci. 2002 Jun;963:282-9. 9. Chen YD, Coulston AM, Zhou MY, Hollenbeck CB, Reaven GM. Why do low-fat high-carbohydrate diets accentuate postprandial lipemia in patients with NIDDM? Diabetes Care. 1995 Jan;18(1):10-6. 10. Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, et al. Effect of a mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004 Sep 22;292(12):1440-6. 11. Singh RB, Dubnov G, Niaz MA, et al. Effect of an Indo-Mediterranean diet on progression of coronary artery disease in high risk patients (Indo-Mediterranean Diet Heart Study): a randomized single-blind trial. Lancet. 2002 Nov 9;360(9344):1455-61. 12. Anderson RA. Essentiality of chromium in humans. Sci Total Environ. 1989 Oct 1;86(1-2):75-81. 13. Available at: http://www.earthsummit.info. Accessed March 9, 2006. 14. Anderson RA, Cheng N, Bryden NA, et al. Elevated intakes of supplemental chromium improve glucose and insulin variables in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1997 Nov;46(11):1786-91. 15. Bahijri SM, Mufti AM. Beneficial effects of chromium in people with type 2 diabetes, and urinary chromium response to glucose load as a possible indicator of status. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2002 Feb;85(2):97-109. 16. Bahijiri SM, Mira SA, Mufti AM, Ajabnoor MA. The effects of inorganic chromium and brewer’s yeast supplementation on glucose tolerance, serum lipids and drug dosage in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Saudi Med J. 2000 Sep;21(9):831-7. 17. Wilson BE, Gondy A. Effects of chromium supplementation on fasting insulin levels and lipid parameters in healthy, non-obese young subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1995 Jun;28(3):179-84. 18. Machalinski B, Walczak M, Syrenicz A, et al. Hypoglycemic potency of novel trivalent chromium in hyperglycemic insulin-deficient rats. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2006;20(1):33-9. 19. Muller M, Grobbee DE, den T, I, Lamberts SW, van der Schouw YT. Endogenous sex hormones and metabolic syndrome in aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 May;90(5):2618-23. 20. Villareal DT, Holloszy JO. Effect of DHEA on abdominal fat and insulin action in elderly women and men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 Nov 10;292(18):2243-8. 21. Ferre P. The biology of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: relationship with lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2004 Feb;53 Suppl 1S43-S50. 22. Delarue J, LeFoll C, Corporeau C, Lucas D. N-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: a nutritional tool to prevent insulin resistance associated to type 2 diabetes and obesity? Reprod Nutr Dev. 2004 May;44(3):289-99. 23. Li H, Ruan XZ, Powis SH, et al. EPA and DHA reduce LPS-induced inflammation responses in HK-2 cells: evidence for a PPAR-gamma-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int. 2005 Mar;67(3):867-74. 24. Madsen T, Skou HA, Hansen VE, et al. C-reactive protein, dietary n-3 fatty acids, and the extent of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2001 Nov 15;88(10):1139-42. 25. Foran SE, Flood JG, Lewandrowski KB. Measurement of mercury levels in concentrated over-the-counter fish oil preparations: is fish oil healthier than fish? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003 Dec;127(12):1603-5. 26. Burger J, Stern AH, Gochfeld M. Mercury in commercial fish: optimizing individual choices to reduce risk. Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Mar;113(3):266-71. 27. Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of insulin resistance in humans and possible links with inflammation. Hypertension. 2005 May;45(5):828-33. 28. Perseghin G, Petersen K, Shulman GI. Cellular mechanism of insulin resistance: potential links with inflammation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Dec;27 Suppl 3S6-11. 29. Comalada M, Camuesco D, Sierra S, et al. In vivo quercitrin anti-inflammatory effect involves release of quercetin, which inhibits inflammation through down-regulation of the NF-kappaB pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005 Feb;35(2):584-92. 30. Donnelly LE, Newton R, Kennedy GE, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol in lung epithelial cells: molecular mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004 Oct;287(4):L774-83. 31. Martinez-Dominguez E, de la PR, Ruiz-Gutierrez V. Protective effects upon experimental inflammation models of a polyphenol-supplemented virgin olive oil diet. Inflamm Res. 2001 Feb;50(2):102-6. 32. Tsuneki H, Ishizuka M, Terasawa M, Wu JB, Sasaoka T, Kimura I. Effect of green tea on blood glucose levels and serum proteomic patterns in diabetic (db/db) mice and on glucose metabolism in healthy humans. BMC Pharmacol. 2004 Aug 26;4:18. 33. Anderson RA, Polansky MM. Tea enhances insulin activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2002 Nov 20;50(24):7182-6. 34. Wolfram S, Wang Y, Thielecke F. Anti-obesity effects of green tea: from bedside to bench. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006 Feb;50(2):176-87. 35. Nakagawa T, Yokozawa T, Terasawa K, Shu S, Juneja LR. Protective activity of green tea against free radical- and glucose-mediated protein damage. J Agric Food Chem. 2002 Apr 10;50(8):2418-22. 36. Wiseman SA, Mathot JN, de Fouw NJ, Tijburg LB. Dietary non-tocopherol antioxidants present in extra virgin olive oil increase the resistance of low density lipoproteins to oxidation in rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 1996 Feb;120(1-2):15-23. 37. Sies H, Stahl W, Sevanian A. Nutritional, dietary and postprandial oxidative stress. J Nutr. 2005 May;135(5):969-72. 38. Carluccio MA, Siculella L, Ancora MA, et al. Olive oil and red wine antioxidant polyphenols inhibit endothelial activation: antiatherogenic properties of Mediterranean diet phytochemicals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003 Apr 1;23(4):622-9. 39. Matthews KA, Rhoten WB, Driscoll HK, Chertow BS. Vitamin A deficiency impairs fetal islet development and causes subsequent glucose intolerance in adult rats. J Nutr. 2004 Aug;134(8):1958-63. 40. Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Giles WH, Brown DW. The metabolic syndrome and antioxidant concentrations: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes. 2003 Sep;52(9):2346-52. 41. Facchini F, Coulston AM, Reaven GM. Relation between dietary vitamin intake and resistance to insulin-mediated glucose disposal in healthy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 Jun;63(6):946-9. 42. Khan A, Safdar M, Ali Khan MM, Khattak KN, Anderson RA. Cinnamon improves glucose and lipids of people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003 Dec;26(12):3215-8. 43. Balachandran B, Sivaramkrishnan VM. Induction of tumours by Indian dietary constituents. Indian J Cancer. 1995 Sep;32(3):104-9. 44. Anderson RA, Broadhurst CL, Polansky MM et al. Isolation and characterization of polyphenol type-A polymers from cinnamon with insulin-like biological activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2004 Jan 14;52(1):65-70. 45. Imparl-Radosevich J, Deas S, Polansky MM, et al. Regulation of PTP-1 and insulin receptor kinase by fractions from cinnamon: implications for cinnamon regulation of insulin signalling. Horm Res. 1998 Sep;50(3):177-82. 46. Jarvill-Taylor KJ, Anderson RA, Graves DJ. A hydroxychalcone derived from cinnamon functions as a mimetic for insulin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001 Aug;20(4):327-36. 47. Qin B, Nagasaki M, Ren M, et al. Cinnamon extract prevents the insulin resistance induced by a high-fructose diet. Horm Metab Res. 2004 Feb;36(2):119-25. 48. Kim SH, Hyun SH, Choung SY. Anti-diabetic effect of cinnamon extract on blood glucose in db/db mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006 Mar 8;104(1-2):119-23. 49. Mancini-Filho J, Van-Koiij A, Mancini DA, Cozzolino FF, Torres RP. Antioxidant activity of cinnamon (Cinnamomum Zeylanicum, Breyne) extracts. Boll Chim Farm. 1998 Dec;137(11):443-7. 50. Tuomilehto J, Hu G, Bidel S, Lindstrom J, Jousilahti P. Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged Finnish men and women. JAMA. 2004 Mar 10;291(10):1213-9. 51. Fukushima M, Matsuyama F, Ueda N, et al. Effect of corosolic acid on postchallenge glucose levels. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006 Mar 18;[Epub ahead of print] 52. Judy WV, Hari SP, Stogsdill WW, Judy JS, Naguib YM, Passwater R. Antidiabetic activity of a standardized extract (Glucosol) from Lagerstroemia speciosa leaves in Type II diabetics. A dose-dependence study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003 Jul;87(1):115-7. 53. Salazar-Martinez E, Willett WC, Ascherio A, et al. Coffee consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Jan 6;140(1):1-8. 54. Zampelas A, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Stefanadis C. Associations between coffee consumption and inflammatory markers in healthy persons: the ATTICA study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Oct;80(4):862-7. 55. Rodriguez de Sotillo DV, Hadley M. Chlorogenic acid modifies plasma and liver concentrations of: cholesterol, triacylglycerol, and minerals in (fa/fa) Zucker rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2002 Dec;13(12):717-26. 56. Johnston KL, Clifford MN, Morgan LM. Coffee acutely modifies gastrointestinal hormone secretion and glucose tolerance in humans: glycemic effects of chlorogenic acid and caffeine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Oct;78(4):728-33. 57. McCarty MF. A chlorogenic acid-induced increase in GLP-1 production may mediate the impact of heavy coffee consumption on diabetes risk. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64(4):848-53. 58. Yen WJ, Wang BS, Chang LW, Duh PD. Antioxidant properties of roasted coffee residues. J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Apr 6;53(7):2658-63. |