Life Extension Magazine®

The American Cancer Society estimates that the majority of colorectal cancers, and subsequent deaths, could be prevented if we applied existing knowledge about this prevalent malignancy.1

Simply making healthy diet and lifestyle choices can reduce the risk for developing colorectal cancer.

With a wealth of research available, too many people continue to needlessly die from this preventable disease.

This article describes strategies available for reducing one’s risk of contracting colorectal cancer, which translates into living a longer, healthier life.

The Most Preventable Cancer

Colorectal cancer (cancer that occurs in the colon or rectum) represents the second leading cause of cancer death in men and women combined in the United States.2,3 According to the American Cancer Society, an approximate 135,000 new cases will be discovered and close to 50,000 deaths will occur in this year alone.4

Despite these statistics, colorectal cancer is one of the most preventable of all cancers. Lifestyle factors play a predominant role in the development of the disease, which means we have a tremendous amount of control over this second-leading cause of cancer deaths.

Cancers in general do not thrive when the body is operating at peak health. This includes active biological systems that work to stop cancer before it even starts by preventing and repairing DNA damage, identifying and destroying abnormal cells, and regulating normal cell growth. The best way to keep these systems in peak condition is through healthy diet and lifestyle choices, as well as incorporating a supplement regimen that includes powerful chemopreventive agents.

The authors of a study published in Clinical Colorectal Cancer said, “Improving the awareness of the population with regard to the benefits of a healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet associated with exercise, could globally reduce CRC (colorectal cancer) risk.”5

A “healthy lifestyle” can include something as simple as regular brisk walking, which has been shown to reduce colorectal cancer risk by 18%-24%.6,7

The reason why exercise is always near the top of any health-optimization regimen is because increased physical activity significantly improves insulin resistance, and also improves levels of inflammatory mediators and inappropriate growth factors. All of these factors, if left untreated, tend to promote cancer development.5,8

Importance of Diet on Colorectal Cancer Incidence

Even more vital than exercise, diet is known to be one of the most important aspects of reducing colon cancer risk. 9-11 While dietary factors can impact all cancer types, they are especially critical in colorectal cancer because of the function and location of the large intestine (which includes the colon and rectum).

All food and drink that enters the body and has to be eliminated must pass through the large intestine. This exposes cells that line the large intestine to carcinogens that either directly damage DNA, or that increase inflammation, which causes free radicals that also damage DNA.

Eating foods cooked at very high temperatures, as Life Extension Magazine® has warned readers about for decades, can cause the formation of cancer-causing chemicals that damage cells of the large intestine.

Studies show that there are numerous foods (or components of foods) that are associated with increased colorectal cancer risk.6,9,11 These include red and processed meats, preserved foods, saturated fats, high-sugar foods, and refined carbohydrates (“white” starches).

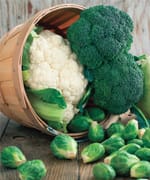

Numerous dietary factors have been shown to have a protective effect against colorectal cancer. These include regular consumption of calcium, vitamin D, fruits, vegetables (especially cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts), fiber, and fish.6,9

More specifically, regular fish consumption reduces the risk of colorectal cancer by 12%, and eating fish while ingesting more than 20 grams per day of fiber can reduce risk by 25%.6

What You Need to Know

|

Powerful Chemoprevention for Colorectal Cancer

- Colorectal cancers are the third most common cancer and the second deadliest cancer among US adults.

- Aggressive screening with colonoscopy has reduced rates of colorectal cancers and the resulting death rates, but even aggressive screening misses thousands of cases annually.

- Prevention is always better than treatment, and for colon cancer multiple nutrients are available that can slow or prevent colorectal cancer development.

- Several drugs, especially metformin, also show strong cancer chemopreventive effects.

- Given the clear and present risk of colorectal cancers in all of our lives, it makes sense to construct and follow a cancer-prevention strategy that includes lifestyle and diet changes as well as a thoughtful supplement regimen.

Cancer-Fighting Nutrients

A glance at the protective dietary factors above reveals that plants and fish products play an especially large role in colorectal cancer prevention. This is due in large part to the abundance of protective molecules that these organisms produce, including vitamins and a host of other biologically active compounds.

While healthy diet is critical, nutrient supplements also provide many compounds shown to help guard against cancer. The use of supplements to reduce the risk of cancer (known as chemoprevention) shows promise for preventing, slowing, and even reversing colon cancer development.

Here is a list of some of the best-studied nutrients in this area:

Higher vitamin D levels are associated with reduced colorectal cancer incidence and deaths. This is likely because vitamin D has immune-supportive functions that can boost the activity of cells that seek and destroy early cancer cells. Vitamin D also reduces the chronic inflammation that can promote colorectal cancer development.12

Studies show that vitamin E, especially in the form of gamma-tocotrienol, reduces colorectal cancer cell growth and even induces tumor cell death.13,14 In addition, vitamin E has strong free radical scavenging properties that may prevent DNA mutations from occurring to begin with.15

Folic acid is important in protecting DNA strands from damage, and has been shown to reduce colorectal cancer risk by 42% in people with inflammatory bowel disease, a group at high risk for this type of cancer.16

Minerals, particularly calcium and selenium, also appear to factor heavily in colon cancer prevention.12 In a large Korean study, people in the highest 25% of calcium intake had an impressive 84% reduction in colon cancer risk, compared with those in the lowest 25% of intake.17 Lab studies reveal that selenium compounds can induce autophagy, a form of cancer cell death in which cells simply destroy themselves. This powerful mechanism is currently being targeted by drug developers.18

Fish oil, rich in omega-3, is a potent inhibitor of inflammation throughout the body, making it a natural fit for colon cancer prevention.19,20 Human studies demonstrate that supplementation with the omega-3 EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid, 2 grams daily for 30 days prior to surgery for colorectal cancer) can reduce the formation of new blood vessels essential for tumor growth, and appeared to produce some increases in overall survival for the first 18 months post-operatively.21

N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) is a strong, natural, free radical scavenger compound, making it appealing for use in cancer prevention of the colon.22 Studies have shown that people at risk for colorectal cancer who took NAC supplements, 600 mg per day, had a 40% reduction in the recurrence of colonic polyps.22 Biochemical and microscopic studies reveal that NAC augments the function of mitochondria (powerhouse of our cells), and produces microscopically detectable changes in early colon cancer in animals.23

As beneficial as they are when taken separately, taking certain nutrients in combination has been shown to have additional value in colorectal cancer prevention. In a large clinical study, the combination of vitamins A, C, and E, along with the element selenium (200 micrograms), reduced the recurrence rate of precancerous polyps by 39%.24 Daily multivitamin use was associated with an 8% reduction in colorectal cancer risk compared with nonusers.25

Cimetidine Prevents Colon Cancer Metastasis and Increases Survival

Cimetidine, commonly known as Tagamet®, is a well-known over-the-counter medication used historically to alleviate heartburn. A growing body of evidence has shown that it also has potent anti-cancer ability. It functions via several mechanisms to inhibit metastasis and improve survival in colon cancer patients.68-75

A study published in the British Journal of Cancer showed cimetidine’s potent anti-cancer effects. For the study, 64 colon cancer patients received chemotherapy with or without cimetidine (800 mg per day) for one year. For the cimetidine group, the 10-year survival was close to 90% compared to only 49.8% for the control group. Remarkably, for those subjects with a more aggressive form of colon cancer, the 10-year survival was 85% in those treated with cimetidine compared to 23% in the control group.74 These findings were confirmed in another study in which colorectal cancer patients were given cimetidine for just seven days at the time of their surgery, and 3-year survival increased from 59% to 93%.75

Cimetidine does not reduce colon cancer incidence, so it should not be taken for prevention purposes. It has demonstrated powerful treatment benefits in those who contract colon cancer. Colon cancer patients should consider taking 800 mg per day of cimetidine five days prior to surgical removal of their tumor and for one year after surgery to reduce metastatic risk. Some people take a 2-3 month course of cimetidine once a year to boost natural killer cell activity.

The Protective Power of Plant-Based Nutrients

Phytonutrients are components of plants thought to promote human health. They help protect plants from dangers such as UV radiation and insect attacks. They also confer protection to those who consume the plants.

Not surprisingly, plant-based nutrients have multiple protective effects against colon cancer. We’ve included a summary of some of the best-studied phytonutrients.

Garlic, especially aged garlic, suppresses the excessive cell proliferation that occurs in the earliest stages of colon cancer. One animal study showed that supplementation with aged garlic extract significantly reduced the development of aberrant crypt foci (precursors of cancer).26 It also reduced the total number of polyps and cancers that formed, a finding that was replicated in humans with a dose of 2.4 mL (approximately half a teaspoon of liquid aged garlic extract) per day for one year.27 Human studies show a 37% reduction in colorectal cancer risk in people with the highest garlic consumption.28

Ginger has effects similar to those of garlic, especially by blocking cell replication and boosting cancer cell self-destruction.29-32 Doses of ginger at 2 grams per day have produced significant favorable changes in the intestinal lining cells of people at increased risk for colorectal cancer.29

Milk thistle extracts, particularly silibinin and silymarin, have numerous mechanisms that help prevent cancers from forming. These include triggering cancer cell suicide (apoptosis), reducing inflammatory changes, and blocking cell replication. Importantly, they also help prevent the spread of existing cancers by reducing the production of protein-melting enzymes that cancer cells use to invade and metastasize.33-35

Cruciferous vegetable extracts are those derived from broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, and related plants. These extracts are rich in molecules called isothiocyanates, which have been shown to promote cancer cell suicide and inhibit colorectal cancer development in animal and lab models.36,37 Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) is another component of these plants that has been shown to reduce inflammation and attenuate colorectal tumor development in animal models. Human studies show that those with higher levels of indole-3-carbinol have significantly lower colorectal cancer risk.38-41

Modified citrus pectin is a gel-like compound extracted from citrus peels that has direct tumor-killing effects on cancer cells. More importantly, animal studies show that it significantly prevents the spread of colorectal cancers to other parts of the body.42,43 This effect arises from pectin’s ability to bind to and block adhesion molecules that metastatic tumor cells use to stick to, and invade, distant tissues.42,43 (Modified citrus pectin is usually taken by those already stricken with cancer. It is not considered a preventive.)

Coffee is rich in numerous bioactive molecules that appear to have anti-cancer properties, such as inducing cancer cell suicide.44,45 Studies show that people with the highest coffee consumption (more than 3 cups per day) have a 33%-79% reduction in their risk for colorectal cancers compared to the lowest consumers.46,47

Understanding Colorectal Cancer

|

Cancers of the colon and rectum are collectively referred to as colorectal cancer. Both structures have similar cellular linings, which is where cancers arise. Although colorectal cancer has numerous causes, these all boil down to chronic chemical stress, inflammation, and loss of control over cell division common to all cancers.

Like all other types of cancer, colorectal cancer begins when DNA damage leads to mutations that deregulate DNA replication.76,77 This causes cells to begin to multiply out of control, which can lead to cancer. Colorectal cancer typically begins as a precancerous growth called a polyp (also known as an adenoma).78-80 Over time, inflammation and oxidative stress can cause benign polyps to progress to a specific kind of cancer called adenocarcinomas.76,81 This type of cancer can be especially dangerous because it is known for spreading to other parts of the body.

Colorectal cancer is typically a silent disease. By the time it produces noticeable symptoms (diarrhea, constipation, bloody stools), the disease is often already in its advanced stages. This highlights the importance of having a routine colonoscopy, which is associated with a 77% mortality risk reduction over 10 years.82 But these screenings are not foolproof.

While it’s true that colonoscopies have sharply reduced the death rates from colorectal cancers, we are still missing far too many dangerous colorectal cancers, often until it is too late.

That’s why prevention is so important. Experts agree that lifelong colon health may be promoted safely, effectively, and naturally using cutting-edge, low-cost nutritional therapies.83

Polyphenols Reduce Cancer Risk

Among the largest group of plant-based nutrients with demonstrated cancer-fighting potential is the polyphenol family.48 Numerous epidemiological studies offer solid evidence that diets rich in polyphenols result in significantly lower incidence for many kinds of cancer—including colon cancer.49,50

Three of the most potent polyphenols with colon cancer-preventive effects are resveratrol, quercetin, and curcumin.

Resveratrol is found in grape skins and other red-pigmented foods. It is one of the best-known polyphenols—and for good reason. It has actions against multiple stages of the cancer-development process that make it a potent chemopreventive agent. Resveratrol is a gene-modifying agent that enhances cells’ resistance to oxidant- and inflammation-promoting stresses.51 It has multiple, complementary effects on colon cancer development, including switching “on” a tumor suppressor gene that gets switched “off” early in carcinogenesis and inhibiting genes for invasion-promoting proteins.52 Preliminary human studies show that oral doses of resveratrol, ranging from 500 to 5,000 mg per day, achieve levels in the intestine consistent with anti-carcinogenic effects.53,54 For people ingesting a wide variety of polyphenols from their healthy diet and supplements, lower doses (100 to 250 mg per day) of resveratrol may be all that is needed.

Quercetin is found in apples and onions. It has been shown to stop the cancer cell replicative cycle and is strongly associated with a reduction in inflammatory molecules that promote cancer development.55,56

Curcumin is what gives the Indian spice turmeric its yellow color. This phenolic compound has an impressive suite of anti-cancer properties that prevent or fight cancer at multiple stages of the development process.57 It blocks inflammation that promotes cancer progression, it stops the cancer cell replication cycle in its tracks, it increases the rate of cancer cell self-destruction, and it prevents tumor cells from developing invasive and metastatic potentials.58-60 In addition, lab studies reveal its ability to inhibit the recently-discovered cancer stem cells, which hide in tissues and are a major cause of cancer recurrence after treatment.61 And a human clinical trial showed that curcumin, 4 grams per day for 30 days, significantly reduced the number of precancerous lesions found on colonoscopy, compared with controls. 62 (Those obtaining nutrients from healthy diets and supplements usually need only 400 mg per day of highly absorbable curcumin.)

Drugs that Prevent Colorectal Cancer

Several pharmaceutical agents are showing signs of effectiveness in preventing colorectal cancers. Aspirin has been associated with a reduction in colorectal cancer incidence and deaths, even at the low doses used for cardiovascular disease protection (75 to 100 mg per day).63 One very large, long-term study has shown that regular aspirin use is associated with as much as a 19% reduction in colorectal cancer rates.64 Unfortunately, most doctors overlook aspirin’s cancer-preventive properties.

Metformin is an antidiabetic drug with a longstanding safety record and a suite of actions more similar to natural supplements with multiple targets than to most single-targeted drugs (indeed, it is derived from the French Lilac tree). Because diabetes is a major risk factor for colorectal cancer, there has been great interest in metformin for cancer prevention, both in diabetes patients and in others.65 A study demonstrated that metformin use is associated with a 10% reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancers and a 32% increase in survival, compared with nonusers.66 In another study, metformin at a dose of 250 mg daily showed a 40% reduction in the prevalence of precancerous adenomas.67

Summary

Colorectal cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer deaths.

Colorectal cancer risk may be greatly reduced through a combination of lifestyle and diet interventions.

A number of nutritional supplements have demonstrated colorectal cancer-preventive properties. These supplements are well-tolerated and widely available, and can form the backbone of a thoughtful, long-term, overall disease prevention strategy.

If you have any questions on the scientific content of this article, please call a Life Extension® Wellness Specialist at 1-866-864-3027.

References

- Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/documents/document/acspc-042280.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Available at: http://www.ccalliance.org/get-information/what-is-colon-cancer/statistics. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/patient/colorectal-prevention-pdq#section/all. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/detailedguide/colorectal-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Aran V, Victorino AP, Thuler LC, et al. Colorectal cancer: Epidemiology, disease mechanisms and interventions to reduce onset and mortality. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016.

- Baena R, Salinas P. Diet and colorectal cancer. Maturitas. 2015;80(3):258-64.

- Golshiri P, Rasooli S, Emami M, et al. Effects of physical activity on risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:32.

- Lee DH, Kim JY, Lee MK, et al. Effects of a 12-week home-based exercise program on the level of physical activity, insulin, and cytokines in colorectal cancer survivors: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2537-45.

- Azeem S, Gillani SW, Siddiqui A, et al. Diet and colorectal cancer risk in Asia--a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(13):5389-96.

- Millen AE, Subar AF, Graubard BI, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and prevalence of colorectal adenoma in a cancer screening trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(6):1754-64.

- Tarraga Lopez PJ, Albero JS, Rodriguez-Montes JA. Primary and secondary prevention of colorectal cancer. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2014;7:33-46.

- Meeker S, Seamons A, Maggio-Price L, et al. Protective links between vitamin D, inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(3):933-48.

- Zhang JS, Li DM, Ma Y, et al. gamma-Tocotrienol induces paraptosis-like cell death in human colon carcinoma SW620 cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57779.

- Forster GM, Raina K, Kumar A, et al. Rice varietal differences in bioactive bran components for inhibition of colorectal cancer cell growth. Food Chem. 2013;141(2):1545-52.

- Campbell S, Stone W, Whaley S, et al. Development of gamma (gamma)-tocopherol as a colorectal cancer chemopreventive agent. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;47(3):249-59.

- Burr NE, Hull MA, Subramanian V. Folic acid supplementation may reduce colorectal cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease : A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016.

- Han C, Shin A, Lee J, et al. Dietary calcium intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:966.

- Yang Y, Luo H, Hui K, et al. Selenite-induced autophagy antagonizes apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(3):1255-64.

- Sorensen LS, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Rasmussen HH, et al. Effects of perioperative supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids on leukotriene B(4) and leukotriene B(5) production by stimulated neutrophils in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled intervention trial. Nutrients. 2014;6(10):4043-57.

- Ma CJ, Wu JM, Tsai HL, et al. Prospective double-blind randomized study on the efficacy and safety of an n-3 fatty acid enriched intravenous fat emulsion in postsurgical gastric and colorectal cancer patients. Nutr J. 2015;14:9.

- Cockbain AJ, Volpato M, Race AD, et al. Anticolorectal cancer activity of the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid. Gut. 2014;63(11):1760-8.

- Ponz de Leon M, Roncucci L. Chemoprevention of colorectal tumors: role of lactulose and of other agents. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1997;222:72-5.

- Amrouche-Mekkioui I, Djerdjouri B. N-acetylcysteine improves redox status, mitochondrial dysfunction, mucin-depleted crypts and epithelial hyperplasia in dextran sulfate sodium-induced oxidative colitis in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;691(1-3):209-17.

- Bonelli L, Puntoni M, Gatteschi B, et al. Antioxidant supplement and long-term reduction of recurrent adenomas of the large bowel. A double-blind randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(6):698-705.

- Heine-Broring RC, Winkels RM, Renkema JM, et al. Dietary supplement use and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(10):2388-401.

- Jikihara H, Qi G, Nozoe K, et al. Aged garlic extract inhibits 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon tumor development by suppressing cell proliferation. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(3):1131-40.

- Tanaka S, Haruma K, Yoshihara M, et al. Aged garlic extract has potential suppressive effect on colorectal adenomas in humans. J Nutr. 2006;136(3 Suppl):821s-6s.

- Chiavarini M, Minelli L, Fabiani R. Garlic consumption and colorectal cancer risk in man: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(2):308-17.

- Citronberg J, Bostick R, Ahearn T, et al. Effects of ginger supplementation on cell-cycle biomarkers in the normal-appearing colonic mucosa of patients at increased risk for colorectal cancer: results from a pilot, randomized, and controlled trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2013;6(4):271-81.

- Qi LW, Zhang Z, Zhang CF, et al. Anti-colon cancer effects of 6-shogaol through G2/M cell cycle arrest by p53/p21-cdc2/cdc25A crosstalk. Am J Chin Med. 2015;43(4):743-56.

- Tahir AA, Sani NF, Murad NA, et al. Combined ginger extract & Gelam honey modulate Ras/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathway genes in colon cancer HT29 cells. Nutr J. 2015;14:31.

- Wee LH, Morad NA, Aan GJ, et al. Mechanism of chemoprevention against colon cancer cells using combined Gelam honey and ginger extract via mTOR and wnt/beta-catenin pathways. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6549-56.

- Eo HJ, Park GH, Song HM, et al. Silymarin induces cyclin D1 proteasomal degradation via its phosphorylation of threonine-286 in human colorectal cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;24(1):1-6.

- Kauntz H, Bousserouel S, Gosse F, et al. Silibinin, a natural flavonoid, modulates the early expression of chemoprevention biomarkers in a preclinical model of colon carcinogenesis. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(3):849-54.

- Kauntz H, Bousserouel S, Gosse F, et al. Silibinin triggers apoptotic signaling pathways and autophagic survival response in human colon adenocarcinoma cells and their derived metastatic cells. Apoptosis. 2011;16(10):1042-53.

- Chen MJ, Tang WY, Hsu CW, et al. Apoptosis induction in primary human colorectal cancer cell lines and retarded tumor growth in SCID mice by sulforaphane. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:415231.

- Slaby O, Sachlova M, Brezkova V, et al. Identification of microRNAs regulated by isothiocyanates and association of polymorphisms inside their target sites with risk of sporadic colorectal cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65(2):247-54.

- Kim YH, Kwon HS, Kim DH, et al. 3,3’-diindolylmethane attenuates colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1164-73.

- Lerner A, Grafi-Cohen M, Napso T, et al. The indolic diet-derivative, 3,3’-diindolylmethane, induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells through upregulation of NDRG1. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:256178.

- Tse G, Eslick GD. Cruciferous vegetables and risk of colorectal neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66(1):128-39.

- Yang G, Gao YT, Shu XO, et al. Isothiocyanate exposure, glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):704-11.

- Huang ZL, Liu HY. Expression of galectin-3 in liver metastasis of colon cancer and the inhibitory effect of modified citrus pectin. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;28(8):1358-61.

- Liu HY, Huang ZL, Yang GH, et al. Inhibitory effect of modified citrus pectin on liver metastases in a mouse colon cancer model. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(48):7386-91.

- Vitaglione P, Fogliano V, Pellegrini N. Coffee, colon function and colorectal cancer. Food Funct. 2012;3(9):916-22.

- Choi DW, Lim MS, Lee JW, et al. The cytotoxicity of kahweol in HT-29 human colorectal cancer cells is mediated by apoptosis and suppression of heat shock protein 70 expression. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2015;23(2):128-33.

- Budhathoki S, Iwasaki M, Yamaji T, et al. Coffee intake and the risk of colorectal adenoma: The colorectal adenoma study in Tokyo. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(2):463-70.

- Nakamura T, Ishikawa H, Mutoh M, et al. Coffee prevents proximal colorectal adenomas in Japanese men: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015.

- Lambert JD, Hong J, Yang GY, et al. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by polyphenols: evidence from laboratory investigations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(1 Suppl):284s-91s.

- Mahmoud NN, Carothers AM, Grunberger D, et al. Plant phenolics decrease intestinal tumors in an animal model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(5):921-7.

- Volate SR, Davenport DM, Muga SJ, et al. Modulation of aberrant crypt foci and apoptosis by dietary herbal supplements (quercetin, curcumin, silymarin, ginseng and rutin). Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(8):1450-6.

- Buhrmann C, Shayan P, Popper B, et al. Sirt1 is required for resveratrol-mediated chemopreventive effects in colorectal cancer cells. Nutrients. 2016;8(3).

- Yang S, Li W, Sun H, et al. Resveratrol elicits anti-colorectal cancer effect by activating miR-34c-KITLG in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:969.

- Patel KR, Brown VA, Jones DJ, et al. Clinical pharmacology of resveratrol and its metabolites in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70(19):7392-9.

- Howells LM, Berry DP, Elliott PJ, et al. Phase I randomized, double-blind pilot study of micronized resveratrol (SRT501) in patients with hepatic metastases--safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(9):1419-25.

- Bobe G, Albert PS, Sansbury LB, et al. Interleukin-6 as a potential indicator for prevention of high-risk adenoma recurrence by dietary flavonols in the polyp prevention trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010;3(6):764-75.

- Atashpour S, Fouladdel S, Movahhed TK, et al. Quercetin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CD133(+) cancer stem cells of human colorectal HT29 cancer cell line and enhances anticancer effects of doxorubicin. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18(7):635-43.

- Irving GR, Iwuji CO, Morgan B, et al. Combining curcumin (C3-complex, Sabinsa) with standard care FOLFOX chemotherapy in patients with inoperable colorectal cancer (CUFOX): study protocol for a randomised control trial. Trials. 2015;16:110.

- Zhang Z, Chen H, Xu C, et al. Curcumin inhibits tumor epithelialmesenchymal transition by downregulating the Wnt signaling pathway and upregulating NKD2 expression in colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(5):2615-23.

- Rajitha B, Belalcazar A, Nagaraju GP, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappaB translocation by curcumin analogs induces G0/G1 arrest and downregulates thymidylate synthase in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;373(2):227-33.

- Huang YT, Lin YW, Chiu HM, et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis of colorectal cancer stem cells by coupling with CD44 marker. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(11):2247-53.

- James MI, Iwuji C, Irving G, et al. Curcumin inhibits cancer stem cell phenotypes in ex vivo models of colorectal liver metastases, and is clinically safe and tolerable in combination with FOLFOX chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2015;364(2):135-41.

- Carroll RE, Benya RV, Turgeon DK, et al. Phase IIa clinical trial of curcumin for the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(3):354-64.

- Di Francesco L, Lopez Contreras LA, Sacco A, et al. New insights into the mechanism of action of aspirin in the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(35):5116-26.

- Cao Y, Nishihara R, Wu K, et al. Population-wide impact of long-term use of aspirin and the risk for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016.

- Anwar MA, Kheir WA, Eid S, et al. Colorectal and prostate cancer risk in diabetes: Metformin, an actor behind the scene. J Cancer. 2014;5(9):736-44.

- He XK, Su TT, Si JM, et al. Metformin is associated with slightly reduced risk of colorectal cancer and moderate survival benefits in diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(7):e2749.

- Higurashi T, Hosono K, Takahashi H, et al. Metformin for chemoprevention of metachronous colorectal adenoma or polyps in post-polypectomy patients without diabetes: a multicentre double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016.

- Lefranc F, Yeaton P, Brotchi J, et al. Cimetidine, an unexpected anti-tumor agent, and its potential for the treatment of glioblastoma (review). Int J Oncol. 2006;28(5):1021-30.

- Natori T, Sata M, Nagai R, et al. Cimetidine inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses tumor growth. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(1-2):56-60.

- Tomita K, Izumi K, Okabe S. Roxatidine- and cimetidine-induced angiogenesis inhibition suppresses growth of colon cancer implants in syngeneic mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;93(3):321-30.

- Adams WJ, Lawson JA, Morris DL. Cimetidine inhibits in vivo growth of human colon cancer and reverses histamine stimulated in vitro and in vivo growth. Gut. 1994;35(11):1632-6.

- Adams WJ, Lawson JA, Nicholson SE, et al. The growth of carcinogen-induced colon cancer in rats is inhibited by cimetidine. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1993;19(4):332-5.

- Adams WJ, Morris DL, Ross WB, et al. Cimetidine preserves non-specific immune function after colonic resection for cancer. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(12):847-52.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(2):161-7.

- Adams WJ, Morris DL. Short-course cimetidine and survival with colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1994;344(8939-8940):1768-9.

- Mariani F, Sena P, Roncucci L. Inflammatory pathways in the early steps of colorectal cancer development. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(29):9716-31.

- Chong ES. A potential role of probiotics in colorectal cancer prevention: review of possible mechanisms of action. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;30(2):351-74.

- Kowalczyk M, Siermontowski P, Mucha D, et al. Chromoendoscopy with a standard-resolution colonoscope for evaluation of rectal aberrant crypt foci. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148286.

- El Zoghbi M, Cummings LC. New era of colorectal cancer screening. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8(5):252-8.

- Floer M, Meister T. Endoscopic improvement of the adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy - where do we stand in 2015? Digestion. 2016;93(3):202-13.

- Hamilton SR. The adenoma-adenocarcinoma sequence in the large bowel: variations on a theme. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1992;16g:41-6.

- Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, et al. Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy: a population-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):22-30.

- Johnson JJ, Mukhtar H. Curcumin for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2007;255(2):170-81.