Life Extension Magazine®

In response to the failure of quadruple-bypass surgery to keep blood flowing to Bill Clinton’s heart, the Associated Press proclaimed that there is no cure for coronary artery disease.1 As we predicted in the November 2004 issue of Life Extension Magazine®, a lot more than statin drugs would be needed to prevent atherosclerotic plaque from re-occluding the former President’s coronary blood flow. According to his cardiologist, Bill Clinton did everything right since his 2004 bypass, including eating well, exercising, and keeping his blood pressure and cholesterol in check. Despite this, the bypass graft re-occluded at the beginning of this year, necessitating the insertion of two stents to prop the vessel open. Mainstream cardiologists were quoted in the media stating that those undergoing coronary artery procedures often have to return every four to five years for tune-ups, i.e., to reopen newly blocked coronary arteries. One cardiac surgeon bragged that he had performed 10 or 15 different stent procedures on the same patient over a period of time. Bill Clinton’s cardiologist stated that we don’t have a cure for this condition, but we have excellent treatments. These blatant admissions document the inability of conventional doctors to prevent and reverse atherosclerosis. Life Extension® Members Know OtherwiseIn response to Bill Clinton’s heart attack and subsequent need for bypass surgery in 2004, Life Extension reminded its members that atherosclerosis arises from a chronic condition known as endothelial dysfunction. We listed the risk factors that cause endothelial dysfunction and described how members could protect against each and every one of them. The fact that mainstream cardiologists have ‘thrown in the towel’ when it comes to eradicating coronary artery disease reveals how little they pay attention to the published scientific literature. Life Extension® members long ago were made aware of 17 independent causes of atherosclerotic disease. The diagram on page 16 of this issue outlines each of these correctable cardiac risk factors. Coronary Artery Disease Can Be Reversed

Contrary to what mainstream cardiologists say, it is possible to reverse the blockage of blood flow through the coronary arteries. One way is to follow the aggressive lifestyle modification program Dean Ornish, MD has prescribed for decades. Dr. Ornish and colleagues showed that a regimen that emphasized a very low fat diet, regular exercise, meditation, and avoidance of certain risk factors not only stopped the progression of coronary artery disease, but could reverse it. This result was demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial, known as the Lifestyle Heart Trial, with data published in The Lancet in 1990. In this study, test subjects were recruited with pre-existing coronary artery disease.2 The patients assigned to Dr. Ornish’s regimen had fewer cardiac events than those who followed standard medical advice.3 What’s more, their coronary atherosclerosis was somewhat reversed, as evidenced by decreased narrowing of the coronary arteries after only one year of treatment. Most patients in the control group, on the other hand, had worsening of their coronary artery blockage at the end of the trial compared to when they started. These favorable results have been replicated by doctors using similar methods (for example, Caldwell B Esselstyn, Jr., MD4 and K. Lance Gould, MD).5 The drawback to Dean Ornish’s program is that it is very restrictive. Participants must avoid all meat and dairy products except egg whites, nonfat milk, and nonfat yogurt; as well as all vegetable oils, nuts, seeds, and avocados. Participants following the Ornish program must supplement with calcium, iron, vitamin B12, and essential fatty acids or deficiencies will develop. As you’ll read soon, there are other documented ways to maintain healthy coronary artery blood flow that are ignored by most practicing cardiologists. Dick Cheney Does Opposite of What Dr. Ornish RecommendsPerhaps no living political figure exemplifies poor lifestyle choices and ensuing chronic heart disease better than former Vice President Dick Cheney.

Cheney was known for eating outrageous quantities of artery-clogging foods and smoked heavily for 20 years. He almost certainly suffers today from cardiac risk factors that extend beyond his early-life unhealthy habits. Shortly after Bill Clinton’s coronary stents were inserted this year, Dick Cheney suffered his fifth heart attack. The first occurred in 1978, when he was only 37. He suffered his second in 1984 and a third in 1988 before undergoing quadruple bypass surgery to unblock his arteries. His fourth heart attack occurred in 2000. At that time, doctors inserted a stent to open a re-occluded coronary artery. In 2001, doctors implanted a device to track and control Cheney’s heart rhythm. In 2008, he underwent a procedure to restore his heart to a normal rhythm after doctors found that he was experiencing a recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Despite all this, Cheney suffered his fifth heart attack in February 2010. Dick Cheney has reportedly taken statin drugs for nearly two decades. In June 2001, his LDL was an excellent 72 mg/dL, indicating he was taking a high-dose statin drug. This did not, however, prevent him from suffering another heart attack. The former Vice President has had access to the best that conventional cardiology can offer, yet his chronic heart ailments have not abated.6 Cheney’s multi-decade case history presented the media with another opportunity to declare there is no cure for coronary heart disease, something that Dr. Dean Ornish and many others involved in natural healing vehemently disagree with. Crestor® Approved by FDA to Reduce C-Reactive ProteinThe FDA has given pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca a gift worth tens of billions of dollars by allowing their statin drug Crestor® to be the only medication approved to reduce the risk of heart attack in aging men and women with LDL-cholesterol less than or equal to 130 mg/dL, elevated C-reactive protein greater than or equal to 2 mg/L, and at least one other traditional cardiac risk factor (e.g. hypertension, smoking, or family history). Life Extension members were warned long ago about the dangers of excess C-reactive protein in the blood. C-reactive protein is a marker of inflammation. Chronic inflammation, as evidenced by high C-reactive protein blood levels, is one cause of atherosclerosis.7-9 Published studies indicate that elevated C-reactive protein may be a greater risk factor than high cholesterol in predicting heart attack and especially stroke risk.10-14 While generic statin drugs and natural therapies have also been shown to reduce C-reactive protein, the FDA has anointed Crestor® as the only approved drug to treat patients with elevated C-reactive protein who also fit certain age and traditional risk factor criteria. This means that Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies have to pay over $125 for 30 20-mg tablets of Crestor® as opposed to as little as $7.30 for 30 40-mg tablets of generic simvastatin (brand name Zocor®). Crestor® is the most potent statin drug, so some people may require 40 mg of simvastatin to achieve the same results as 20 mg of Crestor®. Both of these doses are higher than what is usually needed to lower LDL (low-density lipoprotein). Statin drug side effects are amplified as the dose escalates, so one can expect that those prescribed high-dose Crestor® (to reduce C-reactive protein) will suffer more liver-muscle damage. An increased risk of type 2 diabetes was recently suggested in statin drug users, which further emphasizes the need to use the lowest effective dose if one chooses to use this class of drug.15 There are other options. The Phony Health Care Cost Crisis

The FDA’s gift to AstraZeneca means that only high-cost Crestor® can be advertised and health insurance-reimbursed for the purpose of reducing cardiac risk in patients with a combination of elevated C-reactive protein, “normal” LDL cholesterol, advancing age, and at least one traditional cardiac risk factor like high blood pressure, smoking, and family history. While AstraZeneca enjoys gargantuan profits, taxpayers will be forking over 17 times more than what a generic of probable equal efficacy would cost. Remember, there is no real health care cost crisis. It is governmental over-regulation of our disease-care system that causes medical prices to be hyper-inflated. Our 500-page book FDA Failure, Deceit and Abuse thoroughly documents this tragedy that politicians still cannot grasp.16 Life Extension has long advocated that those who need statin drugs should use the lowest possible dose. For many people with excess C-reactive protein, the lifestyle modifications you will soon read about (and/or low dose 5-10 mg/day simvastatin) can bring elevated C-reactive protein down to safer ranges. Too Many Statin Drug Users Suffer Heart AttacksPharmaceutical companies have promoted statin drugs as a virtual universal remedy to prevent heart attack. According to conventional guidelines, statin drugs are to be prescribed when LDL blood levels exceed 130 mg/dL and lifestyle modifications like stopping smoking and losing weight fail to bring LDL cholesterol to an optimal level. Life Extension has long argued that LDL levels should be kept below 100 mg/dL in healthy people to optimally protect against atherosclerosis. In certain high-risk cardiac patients, LDL levels need to be suppressed below 70 mg/dL. The high dose used in the Crestor® study pushed median LDL level down 50% to a low of 55 mg/dL from a median of 108 mg/dL at baseline and it reduced C-reactive protein by 37%. Despite these impressive reductions in two proven cardiac risk factors, a significant number of subjects taking Crestor® still suffered “major cardiovascular events.”17 This further exposes the fallacy of relying only on statin drugs to maintain healthy arterial blood flow. Remember Bill Clinton and Dick Cheney took statin drugs for years, but their coronary arteries re-occluded anyway. Crestor® will soon be promoted as a panacea for heart attack prevention. What will not be disclosed in drug advertising, however, is that more than half of the major cardiovascular events in the Crestor® study would occur despite the high-dose use of this drug. In statistical terms, while Crestor® reduced the relative risk of the combined endpoint of heart attack, stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes by 47%, the majority (53%) of these cardiovascular endpoints in this high-risk study group would still take place! What this means is that if you have cardiac risk factors and rely solely on a high-dose statin drug, you are still at significant risk of suffering a heart attack. Why Crestor® Failed to Protect All the Study SubjectsThere are at least 17 independent risk factors involved in the development of atherosclerosis and subsequent heart attack and stroke. Statin drugs do not come close to correcting all of these risk factors. Based on the findings from the Crestor® study, it is obvious that even when LDL (and total cholesterol) is reduced to extremely low levels, too many people still suffer a major cardiovascular event. This study will nonetheless be the basis of a national advertising campaign to tout Crestor®. An analysis of the study findings, however, documents the critical need to correct all known cardiovascular risk factors (including elevated LDL, total cholesterol, and C-reactive protein). We are not vilifying the proper use of statin drugs. For many people with stubbornly high LDL and C-reactive protein levels, they represent an important weapon against arterial disease. Our emphasis is that statin drugs are not the only way to lower LDL and C-reactive protein, and they should not be relied on as the only approach to protect against atherosclerosis. Reducing C-Reactive Protein Requires a Multimodal ApproachLife Extension has reviewed thousands of C-reactive protein blood test results over the years. Our consistent observation is that overweight and obese individuals have stubbornly elevated C-reactive protein levels.18 Our findings were confirmed in a recent study that showed overweight and obese individuals are far more likely to have elevated C-reactive protein. In fact, obese people are three times more likely to have elevated C-reactive protein levels than normal-weight individuals.19,20 C-reactive protein is a marker of chronic inflammation. A large body of evidence correlates chronic inflammatory reactions with the increased risks of cancer,21-23 stroke,24 heart attack,25-27 and dementia.28 People who accumulate excess body fat suffer sharply higher incidences of all these diseases, further validating the importance of maintaining C-reactive protein at optimal ranges.

In the Crestor® study, median C-reactive protein levels were 4.2 mg/L in the Crestor® group, and 4.3 mg/L in the placebo group at baseline.17 Obese individuals can have C-reactive protein levels that are easily double this.29 The biological challenge in overweight people is to combat the excess C-reactive protein made directly by fat cells (adipocytes) and the C-reactive protein made in the liver in response to excess amounts of interleukin-6 expressed in abdominal fat that is dumped directly into the liver. Since obese and overweight individuals spew out C-reactive protein from their liver and fat cells, it is often challenging to bring this lethal inflammatory compound (C-reactive protein) into safe ranges. We are impressed with the data from the Crestor® study showing the reduction in C-reactive protein and major cardiovascular events. Our decade-long evaluation of C-reactive protein blood results, however, prompts us to warn that it will require more than statin drugs to suppress dangerously high C-reactive protein levels prevalent in so many individuals. The good news is that low-cost nutrients and hormones, along with dietary changes, can work as well as statins in reducing deadly C-reactive protein. | |||||||||

Vitamin C Reduces C-Reactive ProteinSoon after the media put the Crestor® clinical trial on the front pages, a study was published showing that 1,000 mg a day of vitamin C reduces C-reactive protein as effectively as some statin drugs.19 In this University of California Berkeley study, participants who received vitamin C and started out with C-reactive protein levels greater than 2 mg/L had 34% lower levels compared with the placebo group after only two months.19,20 This study was done based on previous findings that vitamin C supplements reduce elevated C-reactive protein. This study received scant media coverage. A Healthy Diet Significantly Reduces C-Reactive ProteinEating too much saturated fat or high-glycemic carbohydrates increases C-reactive protein.30,31 One study showed a 39% decrease in C-reactive protein levels after only eight weeks of consuming a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol.32 The study participants also saw reductions in their LDL, total cholesterol, body weight, and arterial stiffness.

So while you may soon see ads promoting the 37% C-reactive protein reduction in response to high dose Crestor®, you should be aware that the same benefit has already been shown in response to healthier eating—with no drugs used. For those who cannot adequately control their food intake, the lipase-inhibitor drug orlistat reduces absorption of dietary fat by 30%.33 A drug called acarbose reduces the number of absorbed carbohydrate calories by inhibiting the glucosidase enzyme.34,35 Both of these drugs lower LDL, triglycerides, glucose, cholesterol and other cardiac risk factors when taken before each meal.34-41 There are over-the-counter dietary supplements that exhibit some of these same effects. Another study shows that eating cholesterol-lowering food works about as well as consuming a very low-fat diet plus statin drug therapy. One study showed a 33.3% reduction in C-reactive protein and 30.9% reduction in LDL in subjects eating a very low-fat diet and taking a statin drug. Those who ate the cholesterol-lowering foods showed a 28.2% reduction in C-reactive protein and a 28.6% reduction in LDL.42 This study showed that eating cholesterol-lowering foods achieved almost the same benefit as those who followed a very low-fat diet and took a statin drug. The cholesterol-lowering foods used in this study include almonds, soy protein, fiber, and plant sterols.42 Few people can follow a rigorous low-fat diet and some people want to avoid statin drugs. Based on this study, those who need to reduce LDL and/or C-reactive protein blood levels can accomplish this by eating cholesterol-lowering foods or taking supplements such as soluble fiber powder before heavy meals. In a study of 3,920 people, subjects who ingested the most dietary fiber were found to have a 41% lower risk of elevated C-reactive protein levels, compared with those who ate the least fiber. The doctors who conducted this study concluded: “Our findings indicate that fiber intake is independently associated with serum CRP concentration and support the recommendation of a diet with a high fiber content.”43 There is an important take-home lesson here for those with high C-reactive protein levels that persist even after initiating statin drug therapy. You may be able to achieve significant additive benefits by making dietary modifications, taking at least 1,000 mg of vitamin C each day, and following other proven ways to quell chronic inflammatory reactions. Sex Hormones and Inflammation in MenAging men are plagued with declining testosterone levels while their estrogen remains the same or even increases. This imbalance often sets the stage for a host of chronic inflammatory disorders, while increasing the amount of abdominal adiposity. For years, we at Life Extension have advised maturing men to restore their free testosterone to youthful ranges (between 20 and 25 pg/mL of blood) and keep their estrogen from getting too high. Ideal estrogen (estradiol) levels in men have been shown to be between 20 and 30 pg/mL of blood.

We have seen countless cases of men with chronic inflammation experience a reversal of their elevated C-reactive protein (and painful symptoms) when a youthful sex hormone profile is properly restored. Independent published studies corroborate our findings that low testosterone and high estradiol predisposes aging men to chronic inflammatory status and higher C-reactive protein.90-92 Pomegranate Restores Coronary Artery Blood FlowIn stating that there is “no cure for heart disease,” the media never bothered to look at the scientific literature, where there is a host of documented natural approaches to reverse clinical markers of atherosclerosis.

In one study, doctors tested a group of heart disease patients to ascertain pomegranate’s effects on inducible angina and the rate of blood flow through the coronary arteries. The entire group was given a baseline stress test to induce angina and an advanced diagnostic technique to measure coronary blood flow. One group of cardiac patients received their medications plus placebo, while the second group received their medications plus pomegranate juice. After three months, coronary blood flow was again measured using the same tests performed at baseline. In the group receiving the pomegranate juice, stress-induced angina episodes decreased by 50%, whereas stress-induced angina increased by 38% in the placebo group.97 When measuring coronary artery blood flow, the placebo group worsened by 17% after three months, whereas coronary blood flow improved by 18% in the pomegranate group. This study showed that daily consumption of pomegranate can improve blood flow to the heart in coronary artery disease patients in a relatively short period of time. The doctors noted that the test they used to measure coronary blood flow was shown to be the best predictor of future heart attack risk. Another study compared one group of patients receiving statin and other drugs to a group who received the same drugs plus pomegranate juice. In the drugs-only group, a measurement of systemic atherosclerosis (carotid intima-media thickness) increased by 9% in a year, whereas the group receiving the drugs plus pomegranate showed a 35% reversal in carotid intima-media thickness.98 One way that pomegranate protects cardiovascular health is by augmenting nitric oxide, which supports the functioning of endothelial cells that line the arterial walls.99 Nitric oxide signals the vascular smooth muscle to relax, thereby increasing blood flow through arteries and veins. In the aforementioned study, pomegranate also protected against atherosclerosis by reducing LDL’s basal oxidative status by an astounding 90% and increasing beneficial paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) by 83%.98 Pharmaceutical companies would pay a lot for a patented compound that performs as well as pomegranate. If such a compound were developed, you would see national TV ads promoting it as the “drug” every American should take to protect against heart attack. Fortunately, pomegranate is a low-cost dietary supplement. You won’t see it advertised by the mass media, but then again, you don’t have to pay inflated prescription drug prices for it.

Coronary Artery Occlusion May Be Controlled with Other NutrientsKyolic® garlic,100-102 GliSODin™ (oral superoxide dismutase complex),103,104 fish oil,105-108 and cocoa polyphenols109-114 have all been shown to improve clinical markers of arterial blood flow. An interesting study compared statin drugs side-by-side with fish oil in patients with heart failure. After a median of 3 years of follow-up, fish oil showed more benefit than statin therapy.115 Fish oil helps promote a shift from small, dense LDL particles (more atherogenic) to larger, “fluffier” LDL particles (less atherogenic), and it functions by numerous other mechanisms to protect against heart attack.116,117 Furthermore, the data showing reduction in sudden cardiac death with omega-3 fatty acids (like fish oil) is far more robust and consistent than what has been found in statin drug clinical trials.118,119 Unlike side effect-prone statin drugs, fish oil seems to help protect against virtually every age-related degenerative disease.107,120-124 Those with LDL levels above 100 mg/dL of blood who cannot lower it with dietary changes or supplements should consider a low dose statin drug and fish oil. Simple Guidelines to Protect Yourself Against Heart Attack and StrokeAt the end of this article is a reprint of our 17 “daggers aimed at the heart” diagram that represents independent risk factors associated with heart attack and stroke. Any one of these daggers can create vascular disease. Regrettably, aging people often suffer multiple risk factors (daggers aimed at their heart) that cause them to die prematurely. Fortunately, the proper blood tests can identify risk factors unique to each individual so that corrective action can be taken before one’s heart or brain is decimated by a catastrophic vascular event. To view the optimal blood levels of cardiac risk markers you should seek to attain, please see our protocol on cardiovascular disease. Multiple studies document that a chronic inflammatory process is directly involved in the degenerative diseases of aging including cancer,125-127 dementia,128-130 stroke,131-133 visual disorders,134,135 arthritis,136-138 liver failure,139,140 and heart attack.141-146

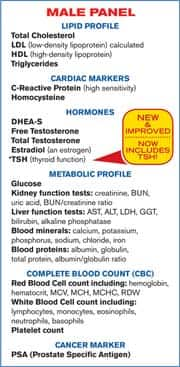

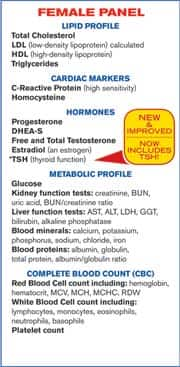

Fortunately, a low-cost C-reactive protein blood test can identify whether you suffer a smoldering inflammatory fire within your body that will likely cause you to die prematurely. An abundance of scientific research provides a wide range of proven approaches to suppress chronic inflammatory reactions.147-165 The comprehensive Male and Female Blood Test Panels reveal your C-reactive protein level, along with other factors that could cause your C-reactive protein to be too high. Blood components that can spike C-reactive protein levels include high LDL,166 low HDL,167 low testosterone168 and excess estradiol (in men),169 elevated glucose,170,171 excess homocysteine,172 and DHEA deficit.173 Optimal blood levels of C-reactive protein are below 0.55 mg/L in men and below 1.50 mg/L in women.174-177 Standard reference ranges accept higher levels as normal because so many people fail to take care of themselves and thus suffer chronically high C-reactive protein levels with subsequently increased risk of heart attack,178-180 stroke,181,182 cancer,125,183 senility,184,185 etc.186

Despite the media portraying cardiac stents as the best choice for those with coronary blockage, a 2007 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine evaluated 2,287 patients over 5 years and found that stents provided no additional benefit over drug cocktails in patients with chronic stable angina (chronic stable coronary artery disease). The study found that stent placement did not affect heart attack risk or coronary mortality.187 Yet these procedures continue to be very popular due to the reimbursement potential ($15,000 per procedure) offered by stent placement to cardiologists. The fact that conventional drug cocktails, bypass grafting, and stents provide such limited benefits emphasizes the need for a comprehensive program to correct all 17 independent cardiac risk factors. Dangers of Relying on the Media for Health InformationToday’s news media function as a mouthpiece for the conventional medical establishment. It is in the economic interests of mainstream cardiology to deceive the public into believing the only way of treating heart disease is with bypass surgery, stents, and drugs. A plethora of published data, however, reveals that aging humans can successfully circumvent the lethal atherosclerotic process and in many cases reverse it. It all starts with comprehensive blood testing. The medical establishment charges around $1,000 for the wide-ranging blood tests needed to assess coronary risk markers. As a Life Extension member, you can obtain the same tests for only $269. When you place your blood test order, we send you a requisition form along with a listing of blood-drawing stations in your area. You can normally walk in during regular business hours for a convenient blood draw. To place your order for the comprehensive Male and/or Female Blood Test Panels, call 1-800-208-3444 or visit www.lifeextension.comhttps://www.lifeextension.com/lpages/labtest2019.

For longer life,

William Faloon

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| References |

| 1. Available at: http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2010-02-12-clinton-heart_N.htm?loc=interstitialskip. Accessed June 14, 2010. 2. Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet. 1990 Jul 21;336(8708):129-33. 3. Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998 Dec 16;280(23):2001-7. 4. Esselstyn CB Jr, Ellis SG, Medendorp SV, Crowe TD. A strategy to arrest and reverse coronary artery disease: a 5-year longitudinal study of a single physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 1995 Dec;41(6):560-8. 5. Sdringola S, Nakagawa K, Nakagawa Y, et al. Combined intense lifestyle and pharmacologic lipid treatment further reduce coronary events and myocardial perfusion abnormalities compared with usual-care cholesterol-lowering drugs in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003 Jan 15;41(2):263-72. 6. Available at: http://www.doctorzebra.com/prez/a_cheney.htm#cholesterol. Accessed April 14, 2010. 7. Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, et al. C-reactive protein and atherosclerosis of the thoracic aorta: a population-based transesophageal echocardiographic study. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Sep 13;164(16):1781-7. 8. Patrick L, Uzick M. Cardiovascular disease: C-reactive protein and the inflammatory disease paradigm: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, alpha-tocopherol, red yeast rice, and olive oil polyphenols. A review of the literature. Altern Med Rev. 2001 Jun;6(3):248-71. 9. Dandona P. Effects of antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic agents on C-reactive protein. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008 Mar;83(3):333-42. 10. Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, Buring JE, Cook NR. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002 Nov 14;347(20):1557-65. 11. Montecucco F, Mach F. New evidences for C-reactive protein (CRP) deposits in the arterial intima as a cardiovascular risk factor. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(2):341-9. 12 Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997 Apr 3;336(14):973-9. 13. Ridker PM, Buring JE, Shih J, Matias M, Hennekens CH. Prospective study of C-reactive protein and the risk of future cardiovascular events among apparently healthy women. Circulation. 1998 Aug 25;98(8):731-3. 14. CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident ischemic stroke in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Nov 28;165(21):2479-84. 15. Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010 Feb 27;375(9716):735-42. 16. Available at: http://www.lifeextension.com/magazine/mag2010/mar2010_How-Much-More-FDA-Abuse-Can-Americans-Tolerate_01.htm. Accessed April 14, 2010. 17. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 20;359(21):2195-207. 18. Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA. 1999 Dec 8;282(22):2131-5. 19. Block G, Jensen CD, Dalvi TB, et al. Vitamin C treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009 Jan 1;46(1):70-7. 20. Available at: http://berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2008/11/12_vitaminc.shtml. Accessed June 15, 2010. 21. Baillargeon J, Rose DP. Obesity, adipokines, and prostate cancer (review). Int J Oncol. 2006 Mar;28(3):737-45. 22. Abu-Abid S, Szold A, Klausner J. Obesity and cancer. J Med. 2002;33(1-4):73-86. 23. Morimoto LM, White E, Chen Z, et al. Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Causes Control. 2002 Oct;13(8):741-51. 24. Ridker PM. Inflammatory biomarkers and risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, and total mortality: implications for longevity. Nutr Rev. 2007 Dec;65(12 Pt 2):S253-9. 25. Bonora E. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Ann Med. 2006;38(1):64-80. 26. Semiz S, Rota S, Ozdemir O, Ozdemir A, Kaptanoglu B. Are C- reactive protein and homocysteine cardiovascular risk factors in obese children and adolescents? Pediatr Int. 2008 Aug;50(4):419-23. 27. Haffner SM. Relationship of metabolic risk factors and development of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006 Jun;14(Suppl 3):121S-127S. 28. Whitmer RA. The epidemiology of adiposity and dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007 Apr;4(2):117-22. 29. Hamer M, Chida Y, Stamatakis E. Association of very highly elevated C-reactive protein concentration with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. Clin Chem. 2010 Jan;56(1):132-5. 30. Petersson H, Lind L, Hulthe J, Elmgren A, Cederholm T, Riserus U. Relationships between serum fatty acid composition and multiple markers of inflammation and endothelial function in an elderly population. Atherosclerosis. 2009 Mar;203(1):298-303. 31. Levitan EB, Cook NR, Stampfer MJ, et al. Dietary glycemic index, dietary glycemic load, blood lipids, and C-reactive protein. Metabolism. 2008 Mar;57(3):437-43. 32. Pirro M, Schillaci G, Savarese G, et al. Attenuation of inflammation with short-term dietary intervention is associated with a reduction of arterial stiffness in subjects with hypercholesterolaemia. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004 Dec;11(6):497-502. 33. Harp JB. Orlistat for the long-term treatment of obesity. Drugs Today (Barc). 1999 Feb;35(2):139-45. 34. Oyama T, Saiki A, Endoh K, et al. Effect of acarbose, an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, on serum lipoprotein lipase mass levels and common carotid artery intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes mellitus treated by sulfonylurea. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008 Jun;15(3):154-9. 35. Hanefeld M, Chiasson JL, Koehler C, Henkel E, Schaper F, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T. Acarbose slows progression of intima-media thickness of the carotid arteries in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Stroke. 2004 May;35(5):1073-8. 36. Henness S, Perry CM. Orlistat: a review of its use in the management of obesity. Drugs. 2006 66(12):1625-56. 37. Rössner S, Sjöström L, Noack R, Meinders AE, Noseda G. Weight loss, weight maintenance, and improved cardiovascular risk factors after 2 years treatment with orlistat for obesity. European Orlistat Obesity Study Group. Obes Res. 2000 Jan;8(1):49-61. 38. Borges RL, Ribeiro-Filho FF, Carvalho KM, Zanella MT. Impact of weight loss on adipocytokines, C-reactive protein and insulin sensitivity in hypertensive women with central obesity. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007 Dec;89(6):409-14. 39. Bougoulia M, Triantos A, Koliakos G. Effect of weight loss with or without orlistat treatment on adipocytokines, inflammation, and oxidative markers in obese women. Hormones (Athens). 2006 Oct-Dec;5(4):259-69. 40. Lucas CP, Boldrin MN, Reaven GM. Effect of orlistat added to diet (30% of calories from fat) on plasma lipids, glucose, and insulin in obese patients with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2003 Apr 15;91(8):961-4. 41. Tzotzas T, Samara M, Constantinidis T, Tziomalos K, Krassas G. Short-term administration of orlistat reduced daytime triglyceridemia in obese women with the metabolic syndrome. Angiology. 2007 Feb-Mar;58(1):26-33. 42. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al. Effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods vs lovastatin on serum lipids and C-reactive protein. JAMA. 2003 Jul 23;290(4):502-10. 43. Ajani UA, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Dietary fiber and C-reactive protein: findings from national health and nutrition examination survey data. J Nutr. 2004 May;134(5):1181-5. 44. Chainani-Wu N. Safety and anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin: a component of turmeric (Curcuma longa). J Altern Complement Med. 2003 Feb;9(1):161-8. 45. Zhang F, Altorki NK, Mestre JR, Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ. Curcumin inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription in bile acid- and phorbol ester-treated human gastrointestinal epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999 Mar;20(3):445-51. 46. Satoskar RR, Shah SJ, Shenoy SG. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory property of curcumin (diferuloyl methane) in patients with postoperative inflammation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1986 Dec;24(12):651-4. 47. Ramsewak RS, DeWitt DL, Nair MG. Cytotoxicity, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of curcumins I-III from Curcuma longa. Phytomedicine. 2000 Jul;7(4):303-8. 48. Pendurthi UR, Williams JT, Rao LV. Inhibition of tissue factor gene activation in cultured endothelial cells by curcumin. Suppression of activation of transcription factors Egr-1, AP-1, and NF-kappa B. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997 Dec;17(12):3406-13. 49. Oben JE, Ngondi JL, Blum K. Inhibition of Irvingia gabonensis seed extract (OB131) on adipogenesis as mediated via down regulation of the PPARgamma and Leptin genes and up-regulation of the adiponectin gene. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;744. 50. Available at: http://stanford.wellsphere.com/healthy-eating-article/more-information-on-irvingia/544189. Accessed March 11, 2010. 51. Ngondi JL, Oben JE, Minka SR. The effect of Irvingia gabonensis seeds on body weight and blood lipids of obese subjects in Cameroon. Lipids Health Dis. 2005 May 25;412. 52. Shea MK, Booth SL, Massaro JM, et al. Vitamin K and vitamin D status: associations with inflammatory markers in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Feb 1;167(3):313-20. 53. Reddi K, Henderson B, Meghji S, et al. Interleukin 6 production by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human fibroblasts is potently inhibited by naphthoquinone (vitamin K) compounds. Cytokine. 1995 Apr;7(3):287-90. 54. Ozaki I, Zhang H, Mizuta T, et al. Menatetrenone, a vitamin K2 analogue, inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth by suppressing cyclin D1 expression through inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Apr 1;13(7):2236-45. 55. Ueda H, Yamazaki C, Yamazaki M. Luteolin as an anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic constituent of Perilla frutescens. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002 Sep;25(9):1197-202. 56. Das M, Ram A, Ghosh B. Luteolin alleviates bronchoconstriction and airway hyperreactivity in ovalbumin sensitized mice. Inflamm Res. 2003 Mar;52(3):101-6. 57. Xagorari A, Papapetropoulos A, Mauromatis A, et al. Luteolin inhibits an endotoxin-stimulated phosphorylation cascade and proinflammatory cytokine production in macrophages. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001 Jan;296(1):181-7. 58. Wu D, Han SN, Meydani M, Meydani SN. Effect of concomitant consumption of fish oil and vitamin E on production of inflammatory cytokines in healthy elderly humans. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004 Dec;1031:422-4. 59. Lo CJ, Chiu KC, Fu M, Lo R, Helton S. Fish oil decreases macrophage tumor necrosis factor gene transcription by altering the NF kappa B activity. J Surg Res. 1999 Apr;82(2):216-21. 60. Caughey GE, Mantzioris E, Gibson RA, Cleland LG, James MJ. The effect on human tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 beta production of diets enriched in n-3 fatty acids from vegetable oil or fish oil. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 Jan;63(1):116-22. 61. Kremer JM. n-3 fatty acid supplements in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Jan;71(1 Suppl):349S-51S. 62. Jolly CA, Muthukumar A, Avula CP, Troyer D, Fernandes G. Life span is prolonged in food-restricted autoimmune-prone (NZB x NZW)F(1) mice fed a diet enriched with (n-3) fatty acids. J Nutr. 2001 Oct;131(10):2753-60. 63. Pischon T, Hankinson SE, Hotamisligil GS, et al. Habitual dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in relation to inflammatory markers among US men and women. Circulation. 2003 Jul 15;108(2):155-60. 64. Madsen T, Skou HA, Hansen VE, et al. C-reactive protein, dietary n-3 fatty acids, and the extent of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2001 Nov 15;88(10):1139-42. 65. Kast RE. Borage oil reduction of rheumatoid arthritis activity may be mediated by increased cAMP that suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001 Nov;1(12):2197-9. 66. Rothman D, DeLuca P, Zurier RB. Botanical lipids: effects on inflammation, immune responses, and rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Oct;25(2):87-96. 67. Izgut-Uysal VN, Agac A, Derin N. Effect of L-carnitine on carrageenan-induced inflammation in aged rats. Gerontology. 2003 Sep;49(5):287-92. 68. Bellinghieri G, Santoro D, Calvani M, Savica V. Role of carnitine in modulating acute-phase protein synthesis in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005 Jan;15(1):13-7. 69. Savica V, Calvani M, Benatti P, et al. Carnitine system in uremic patients: molecular and clinical aspects. Semin Nephrol. 2004 Sep;24(5):464-8. 70. Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Mancuso C, et al. Vitagenes, dietary antioxidants and neuroprotection in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Biosci. 2009 Jan 1;14:376-97. 71. Calabrese V, Giuffrida Stella AM, Calvani M, Butterfield DA. Acetylcarnitine and cellular stress response: roles in nutritional redox homeostasis and regulation of longevity genes. J Nutr Biochem. 2006 Feb;17(2):73-88. 72. Wei DZ, Yang JY, Liu JW, Tong WY. Inhibition of liver cancer cell proliferation and migration by a combination of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and ascorbic acid. J Chemother. 2003 Dec;15(6):591-5. 73. Sanchez-Moreno C, Cano MP, de AB, et al. High-pressurized orange juice consumption affects plasma vitamin C, antioxidative status and inflammatory markers in healthy humans. J Nutr. 2003 Jul;133(7):2204-9. 74. Kaul D, Baba MI. Genomic effect of vitamin ‘C’ and statins within human mononuclear cells involved in atherogenic process. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005 Aug;59(8):978-81. 75. Korantzopoulos P, Kolettis TM, Kountouris E, et al. Oral vitamin C administration reduces early recurrence rates after electrical cardioversion of persistent atrial fibrillation and attenuates associated inflammation. Int J Cardiol. 2005 Jul 10;102(2):321-6. 76. Majewicz J, Rimbach G, Proteggente AR, et al. Dietary vitamin C down-regulates inflammatory gene expression in apoE4 smokers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005 Dec 16;338(2):951-5. 77. Aneja R, Odoms K, Denenberg AG, Wong HR. Theaflavin, a black tea extract, is a novel anti-inflammatory compound. Crit Care Med. 2004 Oct;32(10):2097-103. 78. Pan MH, Lin-Shiau SY, Ho CT, Lin JH, Lin JK. Suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activity by theaflavin-3,3’-digallate from black tea and other polyphenols through down-regulation of IkappaB kinase activity in macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000 Feb 15;59(4):357-67. 79. Liang YC, Tsai DC, Lin-Shiau SY, et al. Inhibition of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced inflammatory skin edema and ornithine decarboxylase activity by theaflavin-3,3’-digallate in mouse. Nutr Cancer. 2002;42(2):217-23. 80. Lin JK. Cancer chemoprevention by tea polyphenols through modulating signal transduction pathways. Arch Pharm Res. 2002 Oct;25(5):561-71. 81. Cai F, Li CR, Wu JL, et al. Theaflavin ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats through its anti-inflammatory effect and modulation of STAT-1. Mediators Inflamm. 2006;2006(5):30490. 82. Siddiqui IA, Adhami VM, Afaq F, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H. Modulation of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-pathways by tea polyphenols in human prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004 Feb 1;91(2):232-42. 83. Ma Y, Hebert JR, Li W, et al. Association between dietary fiber and markers of systemic inflammation in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Nutrition. 2008 Oct;24(10):941-9. 84. Jacobs LR. Relationship between dietary fiber and cancer: metabolic, physiologic, and cellular mechanisms. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986 Dec;183(3):299-310. 85. Galvez J, Rodriguez-Cabezas ME, Zarzuelo A. Effects of dietary fiber on inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005 Jun;49(6):601-8. 86. Qi L, van Dam RM, Liu S, et al. Whole-grain, bran, and cereal fiber intakes and markers of systemic inflammation in diabetic women. Diabetes Care. 2006 Feb;29(2):207-11. 87. Wang XL, Rainwater DL, Mahaney MC, Stocker R. Cosupplementation with vitamin E and coenzyme Q10 reduces circulating markers of inflammation in baboons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Sep;80(3):649-55. 88. Kunitomo M, Yamaguchi Y, Kagota S, Otsubo K. Beneficial effect of coenzyme Q10 on increased oxidative and nitrative stress and inflammation and individual metabolic components developing in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008 Jun;107(2):128-37. 89. Chan YH, Lau KK, Yiu KH, et al. Reduction of C-reactive protein with isoflavone supplement reverses endothelial dysfunction in patients with ischaemic stroke. Eur Heart J. 2008 Nov;29(22):2800-7. 90. Tang YJ, Lee WJ, Chen YT, et al. Serum testosterone level and related metabolic factors in men over 70 years old. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007 Jun;30(6):451-8. 91. Nakhai Pour HR, Grobbee DE, Muller M, Van der Schouw YT. Association of endogenous sex hormone with C-reactive protein levels in middle-aged and elderly men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007 Mar;66(3):394-8. 92. Choi BG, McLaughlin MA. Why men’s hearts break: cardiovascular effects of sex steroids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007 Jun;36(2):365-77. 93. Joyal S. Guard your precious proteins against premature aging. Life Extension. 2008 Apr;14(3):37-43. 94. Vlassara H, Cai W, Crandall J, et al. Inflammatory mediators are induced by dietary glycotoxins, a major risk factor for diabetic angiopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002 Nov 26;99(24):15596-601. 95. Dyer DG, Blackledge JA, Katz BM, et al. The Maillard reaction in vivo. Z Ernahrungswiss. 1991 Feb;30(1):29-45. 96. Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. Glycoxidation and lipoxidation in atherogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000 Jun 15;28(12):1708-16. 97. Sumner MD, Elliott-Eller M, Weidner G, et al. Effects of pomegranate juice consumption on myocardial perfusion in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Sep 15;96(6):810-4. 98. Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Gaitini D, et al. Pomegranate juice consumption for 3 years by patients with carotid artery stenosis reduces common carotid intima-media thickness, blood pressure and LDL oxidation. Clin Nutr. 2004 Jun;23(3):423-33. 99. de Nigris F, Balestrieri ML, Williams-Ignarro S, et al. The influence of pomegranate fruit extract in comparison to regular pomegranate juice and seed oil on nitric oxide and arterial function in obese Zucker rats. Nitric Oxide. 2007 Aug;17(1):50-4. 100. Borek C. Garlic reduces dementia and heart-disease risk. J Nutr. 2006 Mar;136(3 Suppl):810S-812S. 101. Campbell JH, Efendy JL, Smith NJ, Campbell GR. Molecular basis by which garlic suppresses atherosclerosis. J Nutr. 2001 Mar;131(3s):1006S-9S. 102. Efendy JL, Simmons DL, Campbell GR, Campbell JH. The effect of the aged garlic extract, ‘Kyolic’, on the development of experimental atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1997 Jul 11;132(1):37-42. 103. Cloarec M, Caillard P, Provost JC, et al. GliSODin, a vegetal SOD with gliadin, as preventative agent vs. atherosclerosis, as confirmed with carotid ultrasound-B imaging. Allerg Immunol (Paris). 2007 Feb;39(2):45-50. 104. Landmesser U, Spiekermann S, Dikalov S, et al. Vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: role of xanthine-oxidase and extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circulation. 2002 Dec 10;106(24):3073-8. 105. Schmidt EB, Skou HA, Christensen JH, Dyerberg J. N-3 fatty acids from fish and coronary artery disease: implications for public health. Public Health Nutr. 2000 Mar;3(1):91-8. 106. de Mello VD, Erkkilä AT, Schwab US, et al. The effect of fatty or lean fish intake on inflammatory gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with coronary heart disease.Eur J Nutr. 2009 Dec;48(8):447-55. 107. Goodfellow J, Bellamy MF, Ramsey MW, Jones CJ, Lewis MJ. Dietary supplementation with marine omega-3 fatty acids improve systemic large artery endothelial function in subjects with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Feb;35(2):265-70. 108. von Schacky C, Angerer P, Kothny W, Theisen K, Mudra H. The effect of dietary omega-3 fatty acids on coronary atherosclerosis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Apr 6;130(7):554-62. 109. Heiss C, Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, et al. Acute consumption of flavanol-rich cocoa and the reversal of endothelial dysfunction in smokers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Oct 4;46(7):1276-83. 110. Heiss C, Dejam A, Kleinbongard P, Schewe T, Sies H, Kelm M. Vascular effects of cocoa rich in flavan-3-ols. JAMA. 2003 Aug 27;290(8):1030-1. 111. Holt RR, Schramm DD, Keen CL, Lazarus SA, Schmitz HH. Chocolate consumption and platelet function. JAMA. 2002 May 1;287(17):2212-3. 112. Grassi D, Necozione S, Lippi C, et al. Cocoa reduces blood pressure and insulin resistance and improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypertensives. Hypertension. 2005 Aug;46(2):398-405. 113. Baba S, Natsume M, Yasuda A, et al. Plasma LDL and HDL cholesterol and oxidized LDL concentrations are altered in normo- and hypercholesterolemic humans after intake of different levels of cocoa powder. J Nutr. 2007 Jun;137(6):1436-41. 114. Taubert D, Roesen R, Lehmann C, Jung N, Schömig E. Effects of low habitual cocoa intake on blood pressure and bioactive nitric oxide: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Jul 4;298(1):49-60. 115. Marchioli R, Levantesi G, Silletta MG,et al. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and rosuvastatin in patients with heart failure: results of the GISSI-HF trial. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009 Jul;7(7):735-48. 116. Griffin BA. The effect of n-3 fatty acids on low density lipoprotein subfractions. Lipids. 2001;36 Suppl:S91-7. 117. Siddiqui RA, Harvey KA, Zaloga GP. Modulation of enzymatic activities by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids to support cardiovascular health. J Nutr Biochem. 2008 Jul;19(7):417-37. 118. Hu FB, Bronner L, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Rexrode KM, Albert CM, Hunter D, Manson JE. Fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women. JAMA. 2002 Apr 10;287(14):1815-21. 119. Marchioli R, Barzi F, Bomba E, et al. Early protection against sudden death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: time-course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-Prevenzione. Circulation. 2002 Apr 23;105(16):1897-903. 120. Bazan NG. Neuroprotectin D1-mediated anti-inflammatory and survival signaling in stroke, retinal degenerations, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Lipid Res. 2009 Apr;50 Suppl:S400-5. 121. Fradet V, Cheng I, Casey G, Witte JS. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids, cyclooxygenase-2 genetic variation, and aggressive prostate cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Apr 1;15(7):2559-66. 122. Wu M, Harvey KA, Ruzmetov N, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids attenuate breast cancer growth through activation of a neutral sphingomyelinase-mediated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2005 Nov 10;117(3):340-8. 123. Mazza M, Pomponi M, Janiri L, Bria P, Mazza S. Omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in neurological and psychiatric diseases: an overview. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Jan 30;31(1):12-26. 124. Willerson JT, Ridker PM. Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. Circulation. 2004 Jun 1;109(21 Suppl 1):II2-10. 125. Chiu HM, Lin JT, Chen TH, et al. Elevation of C-reactive protein level is associated with synchronous and advanced colorectal neoplasm in men. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep;103(9):2317-25. 126. Groblewska M, Mroczko B, Wereszczynska-Siemiatkowska U, et al. Serum interleukin 6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in colorectal adenoma and cancer patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(10):1423-8. 127. Caruso C, Lio D, Cavallone L, Franceschi C. Aging, longevity, inflammation, and cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004 Dec;1028:1-13. 128. Paganelli R, Di IA, Patricelli L, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines in sera of elderly patients with dementia: levels in vascular injury are higher than those of mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease patients. Exp Gerontol. 2002 Jan;37(2-3):257-63. 129. Zuliani G, Ranzini M, Guerra G, et al. Plasma cytokines profile in older subjects with late onset Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007 Oct;41(8):686-93. 130. Yaffe K, Kanaya A, Lindquist K, et al. The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. JAMA. 2004 Nov 10;292(18):2237-42. 131. Di Napoli M, Papa F, Bocola V. C-reactive protein in ischemic stroke: an independent prognostic factor. Stroke. 2001 Apr;32(4):917-24. 132. Shantikumar S, Grant PJ, Catto AJ, Bamford JM, Carter AM. Elevated C-Reactive Protein and Long-Term Mortality After Ischaemic Stroke. Relationship With Markers of Endothelial Cell and Platelet Activation. Stroke. 2009 Jan 22. 133. Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Jablonski KA, et al. Prognostic significance of the Centers for Disease Control/American Heart Association high-sensitivity C-reactive protein cut points for cardiovascular and other outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007 Mar 27;115(12):1528-36. 134. Boekhoorn SS, Vingerling JR, Witteman JC, Hofman A, de Jong PT. C-reactive protein level and risk of aging macula disorder: The Rotterdam Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007 Oct;125(10):1396-401. 135. Seddon JM, Gensler G, Milton RC, Klein ML, Rifai N. Association between C-reactive protein and age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 2004 Feb 11;291(6):704-10. 136. Joosten LA, Netea MG, Kim SH, et al. IL-32, a proinflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006 Feb 28;103(9):3298-303. 137. Mosaad YM, Metwally SS, Auf FA, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-12 and IL-18) in immune rheumatic diseases: relation with disease activity and autoantibodies production. Egypt J Immunol. 2003;10(2):19-26. 138. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, et al. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003 Jul 22;100(15):9090-5. 139. Antoniades CG, Berry PA, Wendon JA, Vergani D. The importance of immune dysfunction in determining outcome in acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2008 Nov;49(5):845-61. 140. Mani AR, Montagnese S, Jackson CD, et al. Decreased heart rate variability in patients with cirrhosis relates to the presence and degree of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009 Feb;296(2):G330-8. 141. Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, Buring JE, Cook NR. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002 Nov 14;347(20):1557-65. 142. Jialal I, Devaraj S. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: the value of the high-sensitivity C-reactive protein assay as a risk marker. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001 Dec;116(Suppl):S108-15. 143. Kuch B, von Scheidt W, Kling B, et al. Differential impact of admission C-reactive protein levels on 28-day mortality risk in patients with ST-elevation versus non-ST-elevation myocardial. Am J Cardiol. 2008 Nov 1;102(9):1125-30. 144. Jeppesen J, Hansen TW, Olsen MH, et al. C-reactive protein, insulin resistance and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008 Oct;15(5):594-8. 145. Mach F. Inflammation is a crucial feature of atherosclerosis and a potential target to reduce cardiovascular events. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;(170):697-722. 146. Kanda T. C-reactive protein (CRP) in the cardiovascular system. Rinsho Byori. 2001 Apr;49(4):395-401. 147. Ramsewak RS, DeWitt DL, Nair MG. Cytotoxicity, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of curcumins I-III from Curcuma longa. Phytomedicine. 2000 Jul;7(4):303-8. 148. Shea MK, Booth SL, Massaro JM, et al. Vitamin K and vitamin D status: associations with inflammatory markers in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Feb 1;167(3):313-20. 149. Ueda H, Yamazaki C, Yamazaki M. Luteolin as an anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic constituent of Perilla frutescens. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002 Sep;25(9):1197-202. 150. Wu D, Han SN, Meydani M, Meydani SN. Effect of concomitant consumption of fish oil and vitamin E on production of inflammatory cytokines in healthy elderly humans. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004 Dec;1031:422-4. 151. Kremer JM. n-3 fatty acid supplements in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Jan;71(1 Suppl):349S-51S. 152. Jolly CA, Muthukumar A, Avula CP, Troyer D, Fernandes G. Life span is prolonged in food-restricted autoimmune-prone (NZB x NZW)F(1) mice fed a diet enriched with (n-3) fatty acids. J Nutr. 2001 Oct;131(10):2753-60. 153. Pischon T, Hankinson SE, Hotamisligil GS, et al. Habitual dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in relation to inflammatory markers among US men and women. Circulation. 2003 Jul 15;108(2):155-60. 154. Kast RE. Borage oil reduction of rheumatoid arthritis activity may be mediated by increased cAMP that suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001 Nov;1(12):2197-9. 155. Rothman D, DeLuca P, Zurier RB. Botanical lipids: effects on inflammation, immune responses, and rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Oct;25(2):87-96. 156. Izgut-Uysal VN, Agac A, Derin N. Effect of L-carnitine on carrageenan-induced inflammation in aged rats. Gerontology. 2003 Sep;49(5):287-92. 157. Calabrese V, Giuffrida Stella AM, Calvani M, Butterfield DA. Acetylcarnitine and cellular stress response: roles in nutritional redox homeostasis and regulation of longevity genes. J Nutr Biochem. 2006 Feb;17(2):73-88. 158. Korantzopoulos P, Kolettis TM, Kountouris E, et al. Oral vitamin C administration reduces early recurrence rates after electrical cardioversion of persistent atrial fibrillation and attenuates associated inflammation. Int J Cardiol. 2005 Jul 10;102(2):321-6. 159. Majewicz J, Rimbach G, Proteggente AR, et al. Dietary vitamin C down-regulates inflammatory gene expression in apoE4 smokers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005 Dec 16;338(2):951-5. 160. Aneja R, Odoms K, Denenberg AG, Wong HR. Theaflavin, a black tea extract, is a novel anti-inflammatory compound. Crit Care Med. 2004 Oct;32(10):2097-103. 161. Cai F, Li CR, Wu JL, et al. Theaflavin ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats through its anti-inflammatory effect and modulation of STAT-1. Mediators Inflamm. 2006;2006(5):30490. 162. Ma Y, Hebert JR, Li W, et al. Association between dietary fiber and markers of systemic inflammation in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Nutrition. 2008 Oct;24(10):941-9. 163. Qi L, van Dam RM, Liu S, et al. Whole-grain, bran, and cereal fiber intakes and markers of systemic inflammation in diabetic women. Diabetes Care. 2006 Feb;29(2):207-11. 164. Wang XL, Rainwater DL, Mahaney MC, Stocker R. Cosupplementation with vitamin E and coenzyme Q10 reduces circulating markers of inflammation in baboons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Sep;80(3):649-55. 165. Ikonomidis I, Andreotti F, Economou E, et al. Increased proinflammatory cytokines in patients with chronic stable angina and their reduction by aspirin. Circulation. 1999 Aug 24;100(8):793-8. 166. Arena R, Arrowood JA, Fei DY, Helm S, Kraft KA. The relationship between C-reactive protein and other cardiovascular risk factors in men and women. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006 Sep-Oct;26(5):323-7; quiz 328-9. 167. Sampietro T, Bigazzi F, Dal PB, et al. Increased plasma C-reactive protein in familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia: a proinflammatory condition? Circulation. 2002 Jan 1;105(1):11-4. 168. Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, Jones RD, Jones TH, Channer KS. Testosterone as a protective factor against atherosclerosis--immunomodulation and influence upon plaque development and stability. J Endocrinol. 2003 Sep;178(3):373-80. 169. Nakhai Pour HR, Grobbee DE, Muller M, van der Schouw YT. Association of endogenous sex hormone with C-reactive protein levels in middle-aged and elderly men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007 Mar;66(3):394-8. 170. Shankar A, Li J. Positive association between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level and diabetes mellitus among US non-Hispanic black adults. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008 Aug;116(8):455-60. 171. Aronson D, Avizohar O, Levy Y, Bartha P, Jacob G, Markiewicz W. Factor analysis of risk variables associated with low-grade inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 2008 Sep;200(1):206-12. 172. Holven KB, Aukrust P, Retterstol K, et al. Increased levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in hyperhomocysteinemic subjects. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2006; 66(1):45-54. 173. Herman WA, Seńko A, Korczowska I, Lacka K. Assessment of selected serum inflammatory markers of acute phase response and their correlations with adrenal androgens and metabolic syndrome in a population of men over the age of 40. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009 Nov;119(11):704-11. 174. Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein and risk of developing peripheral vascular disease. Circulation. 1998 Feb 10;97(5):425-8. 175. Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4648. Accessed April 30, 2010. 176. Ridker PM. Cardiology Patient Page. C-reactive protein: a simple test to help predict risk of heart attack and stroke. Circulation. 2003 Sep 23;108(12):e81-5. 177. Niu K, Hozawa A, Guo H, et al. Serum C-reactive protein even at very low (<1.0 mg/l) concentration is associated with physical performance in a community-based elderly population aged 70 years and over. Gerontology. 2008;54(5):260-7. 178. Rifai N, Ridker PM. Inflammatory markers and coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002 Aug;13(4):383-9. 179. Albert CM, Ma J, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Ridker PM. Prospective study of C-reactive protein, homocysteine, and plasma lipid levels as predictors of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2002 Jun 4;105(22):2595-9. 180. Bermudez EA, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, statins, and the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Prev Cardiol. 2002; 5(1):42-6. 181. Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident ischemic stroke in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Nov 28;165(21):2479-84. 182. Di Napoli M, Papa F, Bocola V. Prognostic influence of increased C-reactive protein and fibrinogen levels in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2001 Jan;32(1):133-8. 183. Caruso C, Lio D, Cavallone L, Franceschi C. Aging, longevity, inflammation, and cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004 Dec;1028:1-13. 184. Nilsson K, Gustafson L, Hultberg B. C-reactive protein: vascular risk marker in elderly patients with mental illness. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(3):251-6. 185. Komulainen P, Lakka TA, Kivipelto M, et al. Serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein and cognitive function in elderly women. Age Ageing. 2007 Jul;36(4):443-8. 186. Maugeri D, Russo MS, Franze C, et al. Correlations between C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and body mass index during senile osteoporosis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1998 Sep;27(2):159-63. 187. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 12;356(15):1503-16. 188. Ebbing M, Bleie O, Ueland PM, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular events in patients treated with homocysteine-lowering B vitamins after coronary angiography: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Aug 20;300(7):795-804. 189. Jarosz A, Nowicka G. C-reactive protein and homocysteine as risk factors of atherosclerosis. Przegl Lek. 2008;65(6):268-72. |