Life Extension Magazine®

|

| Click Here to Purchase |

Even for those who beat cancer, complete remission is rarely synonymous with a cure without proper follow-up care. In his new book, Life Over Cancer, Dr. Keith Block, widely regarded as the most prominent integrative cancer specialist in the US, has distilled nearly 30 years of clinical experience to reversing the course of cancer and keeping it from returning. Based on the Block Center’s clinical research program, he details how to customize a treatment plan, blending the best conventional approaches with personalized, scientifically based, effective complementary and nutraceutical therapies to keep cancer at bay. In this exclusive excerpt from Life Over Cancer, we reveal just a few of the reasons why the Block Center’s integrative cancer treatment program has helped patients on the road to greater longevity, beyond their original prognoses.

The most effective way to gain control of a systemic disease is to confront it simultaneously at every one of its vulnerable points. If the systemic disorder that allowed cancer to take hold and grow is not eliminated, the cancer may reappear, and with greater resilience than initially. That is what happened to a patient who came to see me after he had been diagnosed with kidney cancer, which his surgeon had removed with a new technique called radiofrequency ablation. Following the procedure, the physician spoke those wonderful words, “You are cancer-free!” You can imagine this man’s shock, then, when he was later diagnosed with metastatic kidney cancer that had spread to his lungs. His doctor’s enthusiasm had left him completely unprepared for the recurrence. My patient felt that he had lost valuable time; assuming his cancer was behind him, he’d never looked into further treatment options. But it was the lack of any attempt to reduce his very real risks of a recurrence that bothered him the most.

That is why Block Center staff members advise patients that even with successful surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy, you deserve and need a follow-up plan and a remission maintenance program to reduce your risk of recurrence. While I believe in the psychological and physical benefits of optimism, I don’t want optimism to get in the way of preparedness. I don’t want you to let down your guard. Although mainstream oncology is excellent at reducing the bulk of visible disease, that is only one part of the battle. Cancer only infrequently disappears after surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. Because some malignant cells are usually left behind, I believe that telling patients they are “cancer-free,” implying that they are through with care, can be detrimental to a full recovery.

This is not to suggest you shouldn’t be relieved and enthusiastic after being pronounced in remission. You certainly should. But you also need to use the period immediately following treatment, when visible disease has been eliminated, to begin a program aimed at mopping up any remaining invisible cells and reducing your odds of ever seeing cancer again.

Just as today no cardiac surgeon would think of sending a patient off after bypass surgery without a referral to a program that teaches diet and exercise, so you should not be sent off after cancer therapy without something to do to help you stay in remission.

Mapping Tumor Growth: The Dynamics of Cancer’s Life Cycle

|

| Click Here to View |

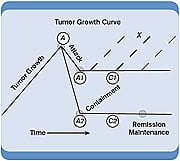

The three major phases of cancer treatment are shown in the figure below. Most cancers are diagnosed where the growth curve peaks, marked A, or just before. By this point, the tumor has been growing and active for quite some time. This is when your physician will implement the attack phase of treatment, which uses some combination of conventional therapies such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and molecular target therapies to reduce or eliminate the tumor. Known as cytoreduction (cyto- means cell), this process is intended to vanquish both the observable tumor and the microscopic individual malignant cells. The result is a steep drop in the tumor growth curve. An effective attack phase brings about either partial remission, shown at point A1 on the chart, or a complete remission, shown at point A2. In a partial remission, evidence of cancer is still visible in scans, X-rays, or MRIs. In a complete remission, there is no visible cancer, although residual cancer cells may lie invisible in the body.

As long as any residual cells remain dormant (whether you have visible disease or not), you can help yourself remain free of clinical disease by utilizing therapies that help control growth. This containment phase is represented by either of the flat lines C1 and C2 in the figure above. Although visible disease may exist (C1) or residual cells may remain (C2), strategies can be implemented to help curb further disease growth or proliferation of leftover residual cells. The containment phase focuses on containing and controlling the growth of these cells with a vigorous application of natural and conventional therapies to provide you with a survivor’s edge.

For those of you in complete remission, congratulations! You will commence on path C2, using the strategies of the containment phase to consolidate your gains and keep any invisible cancer cells from proliferating. However, a word of caution: with some exceptions, even complete remission is rarely synonymous with cure. Returning to your old lifestyle, which may have contributed to your cancer, could also contribute to its return. After being on path C2 for about a year (the exact time depends on your specific circumstances), you can transition from the containment phase to the remission maintenance phase, which uses strategies that are closer to those of cancer prevention. For those of you with a partial remission, my goal is to keep you on path C1, with the hope that you will move toward complete remission, either when our rehabilitation program enables you to return to cytoreductive therapies or when new conventional therapies become available.

It is important to recognize that, as happened to my patient with metastatic kidney cancer, a seemingly successful attack phase may not be a permanent cure. Eliminating the primary tumor may have little or no impact on rogue malignant cells or micrometastases that may have escaped and are setting up camp near the original tumor, in nearby lymph nodes, or in distant organs. These cells have not succumbed to chemo or radiation, usually because they have undergone extreme genetic makeovers that make them resistant to treatment; they can therefore be more aggressive and harder to vanquish than the original tumor. These renegade cells can rear their heads months or even years later, as shown in the upper right quadrant of the figure, the area labeled X. Although the figure shows repopulation occurring after partial remission, it can also occur even years after a complete remission.

It is impossible to know with certainty whether residual cells will sit quiescent in the body until the patient dies of old age or whether they will come roaring back. That’s why I believe in playing it safe, blending conventional oncology, innovative approaches to conventional care, experimental treatments (including immunotherapies and gene therapies), off-label use of medicines, nutrition, supplements, targeted therapies, and lifestyle and mind-spirit approaches to keep residual cells in check.

Attack

|

The goal of attack, or cytoreduction, is to shrink and debulk the tumor and flatten the tumor growth curve with the least amount of toxicity. Our aim is to come as close as possible to eliminating all visible disease. From the perspective of integrative oncology, this is a time when conventional treatments can work synergistically with natural therapies that pack an anticancer wallop. These natural therapies, including complementary nutrition and supplementation, increase the power of conventional therapies while making them safer and less draining so you can tolerate more of a toxic drug with fewer side effects. Skipping doses or lowering dosage, the commonest responses to chemo drug toxicity, means less tumor shrinkage or cancer cell killing. So by including nutrition and supplementation, you can reduce treatment-related toxicity, and improve tumor response and overall survival. By mitigating side effects, you can complete the full course of treatment and thus improve your chance of putting your cancer into remission. Blending mainstream and complementary therapies may lead to results like those [described in this book]: our patients with metastatic breast and prostate cancer used the same radiation, hormones, and chemotherapy drugs as other patients but had median survivals over twice as long as would generally be expected.1 Our results showed a 38-month median survival—an additional eighteen months’ survival—for the breast cancer study, and a 60-month median survival—an additional thirty months—for the prostate cancer group. (Consider that some new drugs are approved on the basis of their lengthening survival by only two to three months.)

The attack phase needs to be carried out in close collaboration with a supportive medical team. At this point your relationship with your treating physician is extremely important; make sure it is one that makes you feel confident and comfortable.

Containment

The goal of the containment phase is to keep the tumor growth curve as flat as possible for as long as possible. Whether you have visible disease or not, containing and controlling cell growth will help you hold the gains you achieved during the attack phase. This is a time to be particularly aggressive, using diet, nutritional therapy, and other integrative therapies. I have seen these strategies work even with patients who had been too debilitated to tolerate further conventional treatment: through an aggressive rehabilitation program, we have been able to assist many of them in getting well enough to return to treatment. These strategies can also help patients whose cancers have resisted conventional treatments: through experimental and off-label drugs, aggressive nutritional therapies, and natural medicines, we have been able to help many patients contain the cancer enough that the patient can live with it as a chronic illness for many years.

Remission Maintenance

If you have achieved complete remission, celebrate! But don’t assume you are out of the woods. Because rogue, resistant cancer cells often remain in the body, you need a long-term program that fights the regrowth of any leftover cells. The longer you are in remission, the better your chances are of beating it back once again if it does recur. If nothing else, the longer you hang in there the more medical breakthroughs you will be able to take advantage of. That is why, in contrast to a focus on just shrinking a tumor, I also put a premium on keeping rogue cells in check. By following a program of remission maintenance, you can improve your odds and reduce the worry that a few cancer cells may remain.

Doug: Life Is Different Now

I know the integrative approach can be a lot to manage when you’re already stressed to the hilt. Unfortunately, in the absence of true cancer cures, we’re forced to confront cancer on its own terms. This wily, multifaceted adversary requires equally wily, multifaceted modes of healing. And your response to cancer needs to be both thorough and lifelong.

In September 1995, in his third week of marriage, twenty-nine-year-old Doug was hit with the awful news that he had a brain tumor, and probably had only six months to live. But he and his wife had a can-do spirit and worked with our center through a grueling road of treatments. Early in his illness, at a routine follow-up meeting, I was explaining to Doug that he needed to make permanent adjustments in the way he was going to live his life. At that point, he looked me in the face, nose to nose, and started shouting and crying, “I want my life back!”

“I know you do,” I replied. That made him start shrieking even louder. “I don’t think you understand—I want my life back!”

I told him calmly but with certainty that regardless of whether or not he was able to overcome his disease, he would never have his old life back the way it was, but it was possible to have a new life.

That’s when Doug said it hit him like a ton of bricks: he and his wife had been viewing his ordeal as if he were training for the Olympics, feeling that once he was victoriously in remission, with his gold medal in hand, the event would be over.

Then they looked at each other and acknowledged instantly that life was never going to be the same as it once was. Life was just different now, and the efforts to keep cancer at bay would have to be lifelong. As of the writing of this book, Doug does continue to thrive and remain cancer-free fourteen years after his original diagnosis.

The Chemotherapy Support Program

Though enthusiastic about our philosophy of care, Gerry was reluctant to begin chemotherapy again. The progression of his disease had left him extremely weak, and he expressed concern about the effects of chemo. When I assured him that we would design a program intended to enhance his treatment tolerance, reduce the toxicity of his treatment, and boost its effectiveness (testing had identified the “molecular fingerprint” of Gerry’s cancer), he agreed to give it a try. His program included therapeutic nutrition to boost stamina, counter fatigue, and reduce chemo’s side effects; mind-spirit interventions to reduce stress; and exercise to build up his strength and fitness. Crucially, we administered the chemo through chronotherapy via an FDA-approved portable pump, small enough to fit in a fanny pack, which delivered supplemental intravenous nutrients at the same time as the chemo drug.

“I couldn’t believe how good I felt throughout my chronotherapy treatments,” Gerry told me later. “Because the pump was portable, I was able to remain active. Having been confined to a hospital room for my previous chemotherapy, this freedom was invigorating.” With each of his scans, Gerry showed improvement. Because he reported no troubling side effects and tolerated his chronotherapy treatments so well, there was no need to reduce the dose. After seven chronotherapy sessions (five fewer than he received of conventional chemotherapy), Gerry showed no evidence of disease, and today in 2009, seven years following his original diagnosis, he is in complete remission and back at work.

Innovative Approaches from Conventional Medicine

Chronotherapy. Timing chemotherapy can increase survival. The reason is that cancer cells are more sensitive to treatment at specific times of night or day.2 Most chemotherapy drugs work best when cancer cells are active and dividing, which makes them most vulnerable to chemo, and are least toxic when healthy cells are at rest. Ideally, then, you would time chemo for this period. Why does chronotherapy lead to fewer side effects than untimed chemo?3 Chemo drugs target dividing cells, because malignant cells are demons of division. But the drugs cannot tell a healthy dividing cell from an aberrantly dividing one, so the former are often also killed. Among the normal cells that are fast-dividing are gastrointestinal cells (whose death by chemo leads to nausea, mouth sores, ulcers, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal effects), bone marrow cells (whose death by chemo leads to dangerous drops in red and white blood cells), and hair follicle cells (whose death leads to balding). But these normal cells divide rapidly only at certain times of day; they all have a resting phase. With chronotherapy, you can receive toxic drugs when cancer cells are actively dividing but normal cells are resting and therefore less likely to be targeted. As you know, if toxic effects get bad enough, your oncologist may be forced to interrupt your treatment, reduce dosing, or stop the treatment altogether, allowing your tumor just the respite it needs to start growing back. That’s not what you want. This is probably one of the reasons why cancer patients getting chronotherapy tolerate treatment better and survive longer than patients getting standard schedules of drug delivery: spared toxic side effects, they can receive the full chemo regimen.4

|

Another reason is that each timed dose of chemotherapy can be more potent than the identical dose of the identical chemo drug given without regard to timing.5 That’s because each cell type and each drug has a period of peak sensitivity. For instance, normal rectal cells divide more often during the day and less at night, so by giving chemotherapy for colon cancer at night we can avoid damaging the normal rectal cells but kill more malignant cells.

Chronotherapy has significantly increased patients’ survival. One 1999 study reported that it increased the five-year survival of patients with advanced ovarian and bladder cancers fourfold, and a multicenter trial in Europe found that patients with advanced metastatic colorectal cancer receiving the chemotherapy drug 5-FU (5-fluorouracil) via chronotherapy had a 50 percent greater median survival time than patients receiving the same drug on a conventional schedule.6 In a 2001 study of chronotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer (stages III and IV), the chronotherapy group had half as many adverse side effects as patients receiving standard chemotherapy; the latter had to have their drug dosages reduced or chemo treatment delayed due to side effects four times as often as the chronotherapy group. This is undoubtedly part of the reason why 44 percent of the chronotherapy group survived for five years compared with 11 percent of the control group.7

A major benefit of chronotherapy is that patients can rechallenge their cancer by using the same drugs in a chronotherapy regimen that they had previously been unable to tolerate with standard dosing. In 2005, the Block Center conducted a study of twenty-six of our colon cancer patients. Six were in stage III and twenty in stage IV; the majority of the stage IV patients received chronotherapy after initial therapy with conventional timing had proved ineffective or intolerable (due to side effects such as mucositis, nausea, and diarrhea severe enough to require treatment in the intensive care unit). But when we gave the patients the same drugs using chronotherapy, none suffered serious toxicity. (In patients like this receiving the same drugs but through standard chemo, the rate of severe toxicity ranges from 24 percent to 65 percent.) What’s more, our twenty stage IV patients had a median survival of twenty-seven months, an excellent record in a disease with a median survival of twelve to eighteen months.8 Let me underline this: if you suffer few to no severe toxic side effects that necessitate stopping or delaying your chemo, you have a better chance at long-term survival.9

Chronotherapy is optimally given over several hours, ratcheting from a minimal dose to a peak dose, and then back down. It is possible to deliver optimally timed chemotherapy in a hospital, so that if your peak sensitivity to a specific drug is, say, 4 A.M. you can receive your peak dose of chemo then. But it is much more convenient to use specialized portable pumps that can be programmed to deliver a drug whenever cancer cells are most susceptible to the drug and normal cells are least vulnerable to its toxicity, as I did with Gerry.

I have used chronotherapy since the 1990s, but as I write there is only one other cancer center in the United States that offers chronotherapy, that run by a pioneer of this field, William Hrushesky, at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Columbia, South Carolina. Europe has at least forty large cancer centers offering chronotherapy. Multiple randomized studies, especially in advanced cancers, have favored chronotherapy over routine infusions, so you may consider receiving treatment using this technique, especially if you have trouble with chemo side effects.10

Fractionated Dose Therapy

|

Traditionally, chemotherapy is given in a single large dose, often as high as a patient can tolerate. This sort of chemo is called bolus dosing. But a number of recent studies show that fractionated or continuous infusion, in which a drug is administered in small doses over the course of a day or several days, is better tolerated and possibly more effective. Although additional clinical studies are needed to confirm this, the better tolerance might improve survival, just as it does with chronotherapy. Ask your oncologists if they have adopted this approach.

Amifostine

We once had a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma who came for care at the center but who could no longer receive a chemotherapy drug, cisplatin, that was making his tumor shrink: it was also causing his kidneys to fail. We put him on the full LOC [Life Over Cancer] program, as well as the conventional drug Ethyol (amifostine), which protects against the renal toxicity associated with cisplatin. Amifostine, which is given by injection, works because it is a potent antioxidant and thus can protect normal tissue from the damaging effects of free radicals, which is how radiation and some chemo drugs exert their cell-killing effects.11 We proceeded with chemotherapy and Ethyol, and he had an excellent response. His kidney function also returned to near normal.

Reprinted with permission, Life Over Cancer, The Block Center Program for Integrative Cancer Treatment by Keith I. Block, MD, published by Bantam Dell, 2009.

The cover price of Life Over Cancer is $25. Life Extension members pay only $17.50.

To order Life Over Cancer, call 1-800-544-4440

1. The Breast Journal. 2009;15(4):in press. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22(abstract):1746.

2. Cancer Lett. 2004;208(2):193-6. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006 Aug;5(8):2023-33.

3. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003 Jun;2(2):105-11. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007 Aug 31;59(9-10):1015-35.

4. Chronobiol Int. 2002 Jan;19(1):237-51.

5. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005 May;91(1):47-60.

6. In Vivo. 1999 Jan-Feb;13(1):77-82. Cancer. 1999 Jun 15;85(12):2532-40.

7. Chronobiol Int. 2002 Jan;19(1):237-51.

8. Block KI, Reynolds S, Gyllenhaal C, et al. Presented at 2nd International Conference of the Society for Integrative Oncology. San Diego, CA, 2005 Nov 10-12.

9. J Clin Oncol. 2006 May 20;24(15):2368-75.

10. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003 Jun;2(2):105-11. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:574-81.

11. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(3):784-91.