Life Extension Magazine®

Prostate cancer is one of the most insidious threats facing aging men today. This devastating disease is now the second leading cause of cancer death among American men after lung cancer. Perhaps the greatest breakthrough in the detection and management of prostate cancer was the approval of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test in 1994. The widespread use of PSA testing led to a notable decline in prostate cancer deaths, but the disease still remains prevalent today. This article reveals further recent advances in PSA testing, which could signal yet another downturn in the incidence of prostate cancer, as more men hopefully will be encouraged to seek screening earlier in life when treatment outcomes for the disease are more likely to be successful. About Prostate CancerAccording to the National Cancer Institute, approximately 220,000 new cases of prostate cancer will be diagnosed this year. During his lifetime, a man has a one in six chance of developing prostate cancer and about one in 10 chance of being diagnosed with the disease.1 This means that more men are affected by prostate cancer than are being diagnosed. These statistics show that prostate cancer is exceedingly common and widespread. In men, it is the most common type of cancer, excluding skin cancer, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Some men are at a higher risk of prostate cancer than others. Studies show that approximately 86% of cases are diagnosed in men between the ages of 55 and 84, signaling that advancing age is a major risk factor for the disease.2 Other risk factors include a family history of prostate cancer, obesity, and being of African-American descent. In fact, African-American men are at least twice as likely to die from the disease than men from other racial and ethnic groups.3 Growing research also shows a correlation between diet and the occurrence of prostate cancer. Men who eat a lot of red meat or high-fat dairy products, who also tend to eat fewer fruits and vegetables, seem to have a greater risk of developing prostate cancer.

PSA and Early DetectionThe facts about prostate cancer are far from comforting, but it is important to remember that prostate cancer is almost 100% survivable if detected early. After receiving approval from the US Food and Drug Administration in 1994, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test, used in complement with the digital rectal exam, has become the primary method used to diagnose prostate cancer in the United States. Although there is still a lot of controversy about this test, who should be screened, and when, it is currently the best screening tool we have for prostate cancer, and has clearly impacted the detection and management of this disease. There is no doubt that the widespread use of this test has led to the tremendous increase in the numbers of cases detected.

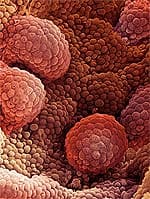

Fortunately, we have also seen an overall downstaging of this disease due to PSA screening, i.e., men who are diagnosed with routine PSA blood testing today are much more likely to have earlier-stage disease than men who were diagnosed in years before the PSA test was widely available. Prior to the PSA era, men were diagnosed with prostate cancer when they had symptoms of metastatic disease, such as bone pain, anemia, weight loss, or obstructive urinary symptoms. Today, most patients have no symptoms at all, and the reason for the prostate biopsy is the PSA test itself, leading to the detection of prostate cancer in its early stages. Recently, this downward stage migration has translated into a reduction in mortality rates for the disease, and the National Cancer Institute noted a 7-10% reduction in prostate cancer-related deaths in 2006. What is PSA?Prostate-specific antigen is a protein produced by the cells of the prostate gland, including both cancerous cells as well as cells that are benign (non-cancerous). It is produced as a component of the ejaculatory fluid and serves the function of liquefying the semen and allowing sperm to swim freely.4 Since very little PSA escapes into the bloodstream from a healthy prostate, an elevated PSA level in the blood indicates an abnormal condition of the prostate gland, which can be either benign or malignant.

Results from a PSA test are used to detect potential problems in the prostate gland, as well as to follow the progress of prostate cancer therapy. The PSA blood test is normally coupled with a digital rectal exam, a procedure during which the doctor inserts a gloved and lubricated finger into the patient’s rectum to feel for nodules and other abnormalities of the prostate. Performed together, these tests considerably increase the chances of detecting prostate cancer in its early stages in men who do not have any symptoms of the disease. Who Should Be Tested?According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), men age 50 and above should have the PSA blood test and the digital rectal exam performed once a year. The ACS also suggests that men who fall into the higher-risk groups (such as African-Americans or men with a family history of the disease) should start the screening process at the age of 40 or 45.5 It is advised that men undergoing a PSA test should refrain from sexual activity for at least 48 hours before the test and that the PSA blood draw be performed before the digital examination in order to prevent higher PSA values and unnecessary worry. How PSA is ReportedThe level of PSA in the blood is measured in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). Until recently, doctors commonly used the PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL as the “cutoff” for screening—anything above would raise concern. However, after recent research showed cancer in men with PSA levels below the 4.0 ng/mL cutoff level, many doctors have adopted the following age-specific reference ranges for screening:6 Others have noted that there is no official “normal” or “abnormal” PSA level. The higher a man’s PSA level, the more likely it is that cancer is present.7 In general, the following guidelines apply to PSA levels:

Because various factors (such as sexual activity) can cause PSA levels to fluctuate, one abnormal PSA test does not necessarily indicate a problem. It should also be noted that normal PSA ranges may vary somewhat among different laboratories. What if the PSA is Elevated?If the PSA is out of range for a patient, my colleagues and I would suggest a repeat exam in a few weeks, as well as a urine test to make sure there is no infection. If the next test remains elevated, a urologist may perform a prostate ultrasound to determine the volume of the gland. Larger glands (i.e., above 40 g) may produce more PSA than smaller glands.

The volume of the gland also determines the PSA density, which compares the amount of PSA in the blood to the size of the prostate measured by ultrasound. In studies at Columbia University, my colleagues and I have found that the lower the PSA density (less than 0.15 ng/mL/cm3), the lower the chance of cancer.7 So if two men both have a PSA of 7 ng/mL, and one man has a gland volume of 80 g, and the other has a volume of 20 g, the man with the smaller gland has a much higher density, and therefore a much higher chance of having cancer. The man with the larger gland has a PSA elevation from benign tissue, and may be spared from undergoing a biopsy. Interestingly, a number of studies have shown that a low PSA does not always mean that there is no cancer; on the other hand, a high PSA does not always mean that there is cancer.8,9 In most cases, a rise in PSA may occur due to conditions such as enlargement of the prostate gland (known as benign prostatic hyperplasia [BPH]), prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate), urinary tract infections, and ejaculation.

One study found that BPH raised average PSA levels in men under the age of 60 who did not suffer from prostate cancer from 0.78 ng/mL to 0.97 ng/mL. In men over the age of 60, BPH raised PSA levels from 1.23 ng/mL to 1.75 ng/mL.10 Due to this tendency, BPH, a disease that commonly affects older men, limits the clinical use of the PSA blood test, as it can raise the PSA nonspecifically.8 Free and Total PSAJust as there is more than one type of lipid in the blood, so too there are multiple forms of PSA. Researchers have found that PSA occurs in two major forms in the blood: free PSA and protein-bound PSA. Adding the free PSA to bound PSA gives the total PSA—the PSA level measured by the common PSA blood test.

One way to determine whether a rising PSA level is due to prostate cancer is to assess the free: total PSA ratio, which is now offered by several labs. Researchers have shown that men who have a higher percentage of free PSA are less likely to have prostate cancer, compared with men who have a lower percentage of free PSA. Many doctors recommend biopsies for men whose free PSA is 10% or less, and advise that men consider a biopsy if it is between 10% and 25%. Using these cutoffs helps detect most cancers, while helping some men avoid unnecessary prostate biopsies, although it should be noted not all doctors agree that 25% is the best “cutoff point” to decide on a biopsy.6,11 PSA VelocityAnother aspect in monitoring PSA levels is the PSA velocity. This refers to how quickly PSA levels increase with time. Even when the total PSA value does not exceed the normal range, a high PSA velocity suggests that cancer may be present and a biopsy should be considered. According to the American Cancer Society, in men whose initial PSA value is less than 4 ng/mL, a PSA velocity of 0.35 ng/mL per year or greater may present reason for concern (for example, if values went from 2.0 to 2.4 to 2.8 ng/mL over the course of two years). For men whose PSA value is between 4 and 10 ng/mL, a biopsy should be more strongly considered if the PSA velocity rises faster than 0.75 ng/mL per year (for example, if values went from 4.0 to 4.8 to 5.6 ng/mL over the course of two years).12 Most doctors believe that PSA levels should be measured on at least three occasions over a period of at least 18 months in order to get an accurate PSA velocity. However, a study published in the April 2006 issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute claims that PSA velocity may not be clinically helpful. Employing sophisticated mathematical analysis, the researchers in this study showed that the PSA level itself is a stronger predictor of prostate cancer than PSA velocity.13

Using PSA to Monitor Prostate Cancer TherapiesPerhaps one of the best uses for PSA is in monitoring the success of prostate cancer therapies. A rising PSA level after a cancer therapy, such as radiation or radical surgery, is usually indicative of a recurrent cancer. Biochemical relapse may occur in patients earlier than the clinical recurrence of the cancer, which serves as the reason for postoperative follow-up and PSA monitoring. Most academic institutions use a PSA value of more than 0.2 ng/mL to define relapse after prostatectomy, although there is some debate about the exact definition. PSA measurements after radiation are less predictable. It generally takes between 12 and 42 months to achieve a nadir PSA—that is, the lowest PSA measurement—after radiotherapy and the nadir value in cured patients may vary because of residual non-cancerous prostate glands. Most men who achieve a durable PSA response attain nadir PSA values of less than 0.5 ng/mL. The American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) has published consensus panel guidelines for testing PSA levels following radiation therapy. These guidelines define biochemical failure as three consecutive rises in PSA following radiotherapy with the date of failure being the midpoint between the PSA nadir and the first PSA rise. Although some modifications have been suggested, these guidelines have standardized the reporting of relapse.14 Not all PSA rises after radiation are due to cancer, and therefore if the patient has three consecutive PSA rises, a prostate biopsy is routinely recommended to determine if the rise is due to cancer. Hormonal Therapy and PSASome evidence suggests that testosterone may act as a promoter or co-inducer of existing prostate cancer.15 A PSA test may therefore be used to monitor the success of hormonal treatment in blocking the production of testosterone in order to limit the growth of prostate cancer cells. Normally, testosterone is produced in response to a cascade of signals beginning in the brain. The hypothalamus produces luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), which travels to the anterior pituitary and stimulates the production of luteinizing hormone (LH). This hormone then travels down to the testicles, where it stimulates the production of testosterone. Doctors therefore use hormonal therapy analogs in the treatment of existing prostate cancers to reduce or stop the production of testosterone. This involves regular injections of LHRH, which cause the body to think that there is too much LHRH in the system, and to become desensitized to the hormone. This negative feedback response causes the anterior pituitary to stop secreting LH, which in turn halts testosterone production.6 There are epidemiological studies, however, that indicate men with higher levels of testosterone do not suffer from an increased risk of prostate cancer,16 but that it is the testosterone metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) that increases the risk of prostate cancer. Since the testosterone metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is ten times more potent than testosterone,17 it is more likely associated with prostate cancer than testosterone. Dihydrotestosterone is produced from testosterone through the action of the enzyme 5-alpha reductase. Thus, it has been proposed that combining a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor (such as dutasteride [Avodart®] or finasteride [Proscar®]) with an LHRH analog drug such as Lupron® may further lower DHT levels within prostate cancer.18 Hormonal therapy works fairly well on hormone-dependent cancers, and, as you might expect, this method is ineffective for hormone-insensitive cancer cells, which do not depend on testosterone for growth. In hormone-dependent cancers, the PSA drops and will usually remain at low levels for an average of two to three years. For men on hormone therapy, the PSA and testosterone levels are both very useful to monitor. The ideal PSA value for men on hormone therapy is <0.1 ng/mL, which indicates that the cancer is not biologically active. It is important for patients and physicians to understand that a zero PSA on hormone therapy does not necessarily mean that the patient is “cancer free.” Hormones can shut off the cancer cells’ ability to make PSA, but the patient may still have cancer. In fact, many aggressive cancer cells can make less PSA, or no PSA at all, and therefore other diagnostic tools, such as a bone scan and CT scan of the pelvis, should be used to monitor the cancer. The amount of time that the PSA remains low on hormone therapy is unknown, and varies based on the extent of cancer and the biological nature of the cells within the tumor. If the PSA starts to rise on hormone therapy, this signals the development of hormone-refractory prostate cancer, i.e., that the cancer has developed androgen insensitivity. These patients should seek the advice from a medical oncologist about the role of other anti-androgens and chemotherapy. Hope for the FutureThere is no question that the PSA test can help spot many prostate cancers early, but there are limits to the current screening methods. Neither the PSA test nor the digital rectal exam is 100% accurate. Uncertain or false test results could cause confusion and anxiety. Some men might have a prostate biopsy when cancer is not present, while others might get a false sense of security from normal test results when cancer is actually present. Despite these limitations, the PSA test is currently the best available tool for detecting and monitoring prostate cancer. If you have any questions on the scientific content of this article, please call a Life Extension Health Advisor at 1-800-226-2370. Dr. Katz is associate professor of urology and director of the Center for Holistic Urology at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. He is the author of Dr. Katz’s Guide to Prostate Health: From Conventional to Holistic Therapies (Freedom Press, 2005).

| |||||||||||||||

| References | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate. Accessed September 10, 2007. 2. Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. 3. Available at: http://planning.cancer.gov/disease/Prostate-Snapshot.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2007. 4. Lilja H, Oldbring J, Rannevik G, Laurell CB. Seminal vesicle-secreted proteins and their reactions during gelation and liquefaction of human semen. J Clin Invest. 1987 Aug;80(2):281-5. 5. Overview: Prostate cancer. American Cancer Society, June 27, 2007. 6. Moyad MA, Pienta KJ. The ABC’s of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Chelseaa, MI: Sleeping Bear Press; 2000. 7. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Detection/PSA. Accessed October 25, 2007. 8. Punglia RS, D’Amico AV, Catalona WJ, Roehl KA, Kuntz KM. Impact of age, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and cancer on prostate-specific antigen level. Cancer. 2006 Apr 1;106(7):1507-13. 9. Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jul 17;349(3):215-24. 10. Lam JS, Cheung YK, Benson MC, Goluboff ET. Comparison of the predictive accuracy of serum prostate specific antigen levels and prostate specific antigen density in the detection of prostate cancer in Hispanic-American and white men. J Urol. 2003 Aug;170(2 Pt 1):451-6. 11. Dittadi R, Franceschini R, Fortunato A, et al. Interchangeability and diagnostic accuracy of two assays for total and free prostate-specific antigen: two not always related items. Int J Biol Markers. 2007 Apr;22(2):154-8. 12. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_3X_Can_prostate_cancer_be_found_early_36.asp. Accessed October 25, 2007. 13. Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Apr 19;98(8):529-34. 14. Taplin ME. Biochemical (Prostate-Specific Antigen) Relapse: An Oncologist’s Perspective. Rev Urol. 2003;5 Suppl 3S3-S13. 15. Shirai T, Takahashi S, Cui L, et al. Experimental prostate carcinogenesis: rodent models. Mutat Res. 2000 Apr;462(2-3):219-26. 16. Severi G, Morris HA, MacInnis RJ, et al. Circulating steroid hormones and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Jan;15(1):86-91. 17. Deslypere JP, Young M, Wilson JD, McPhaul MJ. Testosterone and 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone interact differently with the androgen receptor to enhance transcription of the MMTV-CAT reporter gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992 Oct;88(1-3):15-22. 18. Singh P, Uzgare A, Litvinov I, Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. Combinatorial androgen receptor targeted therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006 Sep;13(3):653-66. 19. Gallardo-Williams MT, Maronpot RR, Wine RN, Brunssen SH, Chapin RE. Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of prostate-specific antigen by boric acid and 3-nitrophenyl boronic acid. Prostate. 2003 Jan 1;54(1):44-9. 20. Cohen P, Graves HC, Peehl DM, et al. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is an insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 protease found in seminal plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992 Oct;75(4):1046-53. 21. Cohen P, Peehl DM, Graves HC, Rosenfeld RG. Biological effects of prostate specific antigen as an insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 protease. J Endocrinol. 1994 Sep;142(3):407-15. 22. Available at: http://www.lifeextension.com/magazine/mag2005/jun2005_awsi_02.htm. Accessed October 26, 2007. 23. Diamandis EP. Prostate-specific antigen: a cancer fighter and a valuable messenger? Clin Chem. 2000 Jul;46(7):896-900. |