Life Extension Magazine®

A 2017 article in the journal Frontiers of Immunology described influenza as a leading cause of catastrophic disability in older adults.1

For some older adults, these infections, which are most common in the depths of winter, can be life-threatening.

Influenza and pneumonia are responsible for more than 57,000 US deaths annually.2

Conventional authorities recommend that older adults get a flu vaccine every year. But because of age-related decline in the immune system (called immune senescence), flu vaccines may not be enough to fight off viral infections on their own.3-5

Searching for an innovative way to reduce the risk of colds and flu, scientists have demonstrated that a specially formulated probiotic cocktail offers targeted prevention. It works to boost the body’s immune defenses against the common cold and flu.6-8

Published studies show that these good bacteria significantly reduce the risk of getting upper respiratory tract infections, including colds and flus. And in those who do get sick, these probiotics reduce the severity and duration of the illness.

While anyone can benefit from additional immune support during cold and flu season, this potent probiotic defense is especially critical for elderly and immune-compromised individuals wishing to avoid potentially serious complications.

What you need to know

- Flu and pneumonia kill more than 57,000 Americans each year, and aging adults are more susceptible to colds and flu—which can lead to pneumonia.

- More than 70% of the human immune system is found in the gut.

- Secretory IgA is a built-in security system present in mucosal membranes that line the nose and upper respiratory tract that can prevent cold and flu viruses from entering our bodies.

- Scientists have shown that six strains of orally ingested probiotic bacteria boost IgA production— enhancing immunity and blocking the virus replication cycle.

- Human trials show that specific probiotics reduce cold and flu-like infections, an effect that may be attributable in large part to increased IgA secretion.

Aging Makes the Flu Virus Potentially Deadly

The influenza virus can have a devastating impact on aging individuals.

At least 90% of the flu-related deaths every year involve people over 65.9 The flu virus can also boost the risk of secondary bacterial infections and can worsen preexisting medical problems.10-12

Most of those hospitalized for flu infections are older adults.13,14 For this group, lengthy hospital stays pose additional health risks.15

In an effort to prevent the flu—and all of the risks associated with it—many older adults dutifully get a flu vaccine every winter. The problem is that the claimed effectiveness of the flu vaccine among aging adults is exaggerated.16

A very recent study found that the vaccine’s effectiveness decreases as the degree of frailty (as measured by the Frailty Index) increases.17 And while the vaccine works in 70%-90% of young adults, that number drops to 17%-53% in older adults.18

Fortunately, there’s a way to boost your body’s own defenses against the cold and flu—and it begins by taking care of your gut. Maintaining a healthy, balanced gut microbiome provides people of all ages with surprisingly strong protection against potentially deadly viruses such as cold and flu.

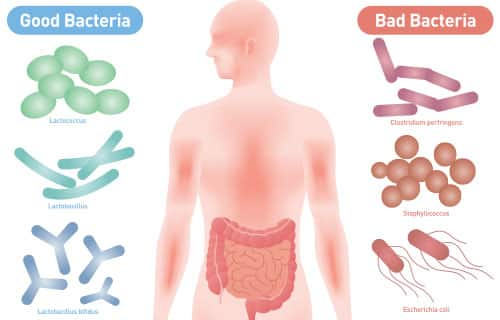

Gut Bacteria Modulate Your Immune System

It’s only been in recent years that scientists have come to recognize the importance of gut bacteria in modulating the immune system. More than 70% of the human immune system resides in the gut.

In addition, the intestinal immune system contains more antibody-producing cells than the rest of the body put together.19 As a result, fluid secreted from the digestive system (such as mucus and saliva) is as rich as breast milk in health-supporting and disease-preventing factors.20

A poorly functioning immune system is at the root of many conditions that aggressively target aging adults. For example, too little immune response makes us vulnerable to the infections that claim the lives of so many older adults. Yet a poorly balanced (overactive) immune system can produce chronic inflammation—contributing to a litany of age-related disorders such as diabetes, cancer, and metabolic syndrome.

Probiotics help restore the balance of your gut microbiome, and can strengthen its ability to interact with your immune system in many ways.21 These friendly bacteria stimulate a healthy immune system, boosting populations of cells that seek out and destroy infecting organisms and cancers.22,23

While probiotics promote immune balance and strength, scientists have found that a specific blend of unique probiotics is especially effective at blocking flu, cold, and other respiratory viruses.

Supporting the Body’s Secretory Immune System

Colds and flu are often treated with medications designed to reduce only the symptoms of these respiratory infections. These drugs can’t activate the body’s own immune response to fend off invading bacteria or viruses.

That’s what makes probiotics different. Probiotics provide defense against the common cold and flu by activating the body’s own immune response.

The immune system makes proteins called antibodies that fight bacteria, viruses, and toxins. One of the most common antibodies, called secretory IgA (immunoglobulin A), is found in mucous membranes. IgA acts as the body’s built-in security system within mucous membranes that line the nose and upper respiratory tract.24-26 When IgA levels are adequate, these antibodies can prevent cold and flu viruses from entering the body through the nasal mucous and respiratory tract.27

Probiotics Block Virus Replication Cycle

Having adequate IgA levels is critical because these antibodies target both viral and bacterial invaders in the upper respiratory tract, deactivating them, and presenting them for destruction by the immune system. This IgA activity prevents cold and flu viruses from gaining a foothold and wreaking havoc on the respiratory tract.28 Once a flu virus infects cells, it can then replicate out of control.29

To counteract this problem, researchers tested a unique oral probiotic blend designed to reduce the risk of respiratory infections by enhancing secretory immunity.

Secretory immunity is the production of specialized antibodies such as IgA in the mucous membranes lining the nose and portions of the windpipe and lungs.30 By increasing IgA secretion and breaking the virus replication cycle, we can prevent colds, influenza, and other respiratory infections.

The ability of an immune-regulating probiotic cocktail to fight off microbes, including viruses that attack the respiratory tract, appears to be due to stimulation of IgA.

Several placebo-controlled, human clinical trials have demonstrated just how powerfully this unique probiotic blend works to prevent infection by cold and flu viruses.

Unique Probiotic Blend Blocks Respiratory Infections

Of the six novel strains of probiotics that make up this respiratory infection-blocking cocktail, five strains were tested together in one clinical study:8

- L. plantarum (LP 01-LMG P-21021),

- L. plantarum (LP 02-LMG P-21020),

- L. rhamnosus (LR 04-DSM 16605),

- L. rhamnosus (LR 05-DSM 19739), and

- B. lactis (BS 01-LMG P-21384).

In a clinical trial during cold and flu season, 250 volunteers were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo or a mixture with these five probiotic strains. Over a period of 90 days, subjects reported daily on all diseases affecting their respiratory system, including cough, colds, bronchitis, or pneumonia, and how long they lasted. They also described their symptoms and the severity of the symptoms.8

Researchers classified these symptoms according to flu-like syndromes (those accompanied by fever), influenza-like illnesses, bronchitis-like diseases, upper respiratory tract infections, common cold, and cough without other symptoms.

Analysis of the data showed that taking these five strains of probiotics dramatically prevented both colds and flu, while also reducing the symptoms and duration of colds in those who did get sick. There were 16 cases of flu in the placebo group, compared to just 3 in the probiotic group.

In addition, taking the probiotic resulted in a:8

- 35% reduction in the number of colds (20 episodes vs. 31 episodes)

- 22% reduction in cold duration (4.7 days vs. 6 days)

- 39% reduction in cough duration (4.5 days vs. 7.3 days)

- 25% reduction in the number of days of acute upper respiratory infections (4.6 days vs. 6.1 days)

A similar study found that the probiotic cocktail resulted in a 48% decrease in the number of flu episodes. And the number of days with flu symptoms dropped by a significant 55%.6

Fortifying the Probiotic Cocktail

Another group of scientists identified a sixth probiotic strain that provides further immune-stimulating effects, specifically among aging adults at risk for respiratory infections:7

- B. subtilis CU1.

Researchers have very recently hypothesized that Bacillus subtilis generates potent probiotic effects, including “the production of antimicrobials, stimulation of the immune system, and overall enhancement of gut microflora.”31

Of all Bacillus bacteria, B. subtilis is the species known to produce the most antimicrobial compounds.32 B. subtilis CU1 is a newly identified strain of this species, and it has been described as “an effective probiotic in healthy elderly subjects.”31

B. subtilis CU1 creates a natural protective shield that resists the acid in the stomach, which helps the probiotic stay alive until it reaches nonacidic conditions, lower in the digestive tract.33 This probiotic strain can stimulate IgA secretion, which provides a critical mechanism for preventing respiratory infections.7,34

Scientists conducted a human clinical trial among healthy older adults during flu season in France. For the study, adults 60-74 years old were randomly assigned to receive either B. subtilis CU1 or a placebo. Participants took one capsule daily, containing two billion microorganisms per capsule.7

The findings not only showed decreased respiratory infections—but also strongly suggested that increased IgA was at least partly responsible for the observed impact. Specifically, there was a:7

- 45% decrease in respiratory infections, and

- 45% increase in concentrations of IgA in subjects’ saliva.

The increase in IgA levels and the corresponding decrease in respiratory infections prompted the authors to attribute these effects to the ability of B. subtilis CU1 to enhance systemic—as well as intestinal and respiratory mucosal—immune responses.7

No significant side effects were observed in either group.7

A later study was conducted specifically to evaluate the safety of B. subtilis CU1. Analysis of both in vitro and clinical studies demonstrated that this strain is nonpathogenic and non-toxicogenic. The study concluded that this strain of B. subtilis is “safe and well-tolerated during repeated consumption in healthy elderly subjects” and is “therefore considered safe and suitable for use as a probiotic ingredient.”31

These studies provide compelling evidence that these six probiotic strains specifically enhance the body’s immune defense against upper respiratory tract infections—a particular risk for older adults who have reduced immune response.

What Should You Do?

Most of our readers take a probiotic supplement for digestive and other health benefits.

For winter months, you may consider switching to an immune-specific probiotic that contains many of the same beneficial bacterial strains, plus additional ones that have shown robust results in recent clinical trials.

Summary

For aging adults, viral cold or flu infections can cause catastrophic disability and lead to bacterial infections such as pneumonia. Flu and pneumonia kill over 57,000 Americans each year.

Robust defenses against respiratory infection require optimal secretory immunity, which depends in large part on antibodies known as IgA.

Six specific strains of orally ingested probiotic bacteria have been shown to stimulate the body’s production of IgA, which protects the delicate mucous membranes, and ultimately helps prevent the virus replication cycle.

Human studies demonstrate that using these six strains of bacteria can reduce the incidence of colds and flu-like illnesses, an effect largely attributable to enhanced levels of IgA.

If you have any questions on the scientific content of this article, please call a Life Extension® Wellness Specialist at 1-866-864-3027.

References

- Merani S, Pawelec G, Kuchel GA, et al. Impact of Aging and Cytomegalovirus on Immunological Response to Influenza Vaccination and Infection. Front Immunol. 2017;8:784.

- Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm. Accessed November 7, 2016.

- Haq K, McElhaney JE. Immunosenescence: Influenza vaccination and the elderly. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;29:38-42.

- Dorrington MG, Bowdish DM. Immunosenescence and novel vaccination strategies for the elderly. Front Immunol. 2013;4:171.

- Weinberger B, Herndler-Brandstetter D, Schwanninger A, et al. Biology of immune responses to vaccines in elderly persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(7):1078-84.

- Belcaro G, Cesarone MR, Cornelli U, et al. Prevention of flu episodes with colostrum and Bifivir compared with vaccination: an epidemiological, registry study. Panminerva Med. 2010;52(4): 269-75.

- Lefevre M, Racedo SM, Ripert G, et al. Probiotic strain Bacillus subtilis CU1 stimulates immune system of elderly during common infectious disease period: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Immun Ageing. 2015;12(1):24.

- Pregliasco F, Anselmi G, Fonte L, et al. A new chance of preventing winter diseases by the administration of synbiotic formulations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42 Suppl 3 Pt 2:S224-33.

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. Jama. 2003;289(2):179-86.

- Zimmerman RK, Lauderdale DS, Tan SM, et al. Prevalence of high-risk indications for influenza vaccine varies by age, race, and income. Vaccine. 2010;28(39):6470-7.

- Loerbroks A, Stock C, Bosch JA, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among high-risk groups in 11 European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(4):562-8.

- Handel A, Longini IM, Jr., Antia R. Intervention strategies for an influenza pandemic taking into account secondary bacterial infections. Epidemics. 2009;1(3):185-95.

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. Jama. 2004;292(11):1333-40.

- Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/2015-16.htm. Accessed November 13, 2017.

- Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/vaccineeffect.htm. Accessed November 12, 2017.

- Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, et al. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: an ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(10):658-66.

- Andrew MK, Shinde V, Ye L, et al. The Importance of Frailty in the Assessment of Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against Influenza-Related Hospitalization in Elderly People. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(4):405-14.

- Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24(8):1159-69.

- Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C, Lycke N, et al. Mucosal immunity: implications for vaccine development. Immunobiology. 1992;184(2-3):157-79.

- Bengmark S. Gut microbial ecology in critical illness: is there a role for prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8(2):145-51.

- Rauch M, Lynch SV. The potential for probiotic manipulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23(2):192-201.

- Pronio A, Montesani C, Butteroni C, et al. Probiotic administration in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis is associated with expansion of mucosal regulatory cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(5):662-8.

- de Moreno de LeBlanc A, Matar C, Perdigon G. The application of probiotics in cancer. Br J Nutr. 2007;98 Suppl 1:S105-10.

- Woof JM, Kerr MA. IgA function--variations on a theme. Immunology. 2004;113(2):175-7.

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AHH, Pillai S. Basic Immunology E-Book: Functions and Disorders of the Immune System. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Available at: http://missinglink.ucsf.edu/lm/immunology_module/prologue/prologue_syllabus_2008.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2017.

- Available at: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx? ContentTypeID=134&ContentID=124. Accessed November 13, 2017.

- Snoeck V, Peters IR, Cox E. The IgA system: a comparison of structure and function in different species. Vet Res. 2006;37(3):455-67.

- Smith AE, Helenius A. How viruses enter animal cells. Science. 2004;304(5668):237-42.

- Fagarasan S, Honjo T. Regulation of IgA synthesis at mucosal surfaces. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(3):277-83.

- Lefevre M, Racedo SM, Denayrolles M, et al. Safety assessment of Bacillus subtilis CU1 for use as a probiotic in humans. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;83:54-65.

- Starosila D, Rybalko S, Varbanetz L, et al. Anti-influenza Activity of a Bacillus subtilis Probiotic Strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(7).

- Cutting SM. Bacillus probiotics. Food Microbiol. 2011;28(2):214-20.

- Corthesy B. Multi-faceted functions of secretory IgA at mucosal surfaces. Front Immunol. 2013;4:185.